518

Volume 63 – Number 3

SMART ROYALTIES: TACKLING THE

MUSIC INDUSTRY’S COPYRIGHT DATA

DISCREPANCIES THROUGH BLOCKCHAIN

TECHNOLOGY, SMART CONTRACTS, AND

NON-FUNGIBLE TOKENS

AMANDA J. SHARP

*†

AND ORLY LOBEL

**

*

J.D. Candidate May 2023, Warren Family Scholarship

Recipient, C. Hugh Friedman Scholarship Recipient, University of San

Diego School of Law; 2021 San Diego County Bar Association

Diversity Fellow; 2023 Entertainment Law Initiative Writing

Competition Runner-Up; 2023 3L Next Gen California ChangeLawyer

Scholar. Thank you to the IDEA Law Review and its members,

specifically Lea Polito, Stephanie Casino, Matthew Arsenault,

Emmeline Drake, Mitchell Gross, Andrea Pelloquin, Andrew

Dominick, and Brittany Reeves for their contributions.

†

IDEA Vol. 63 thanks Amanda Sharp for participating in

IDEA’s Fall 2022 Symposium “IP in the Metaverse: Protecting IP

Rights in the Virtual World.”

**

University Professor, Warren Distinguished Professor of

Law, and Director of the Center for Employment and Labor Policy

(CELP), University of San Diego School of Law.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 519

Volume 63 – Number 3

ABSTRACT

Blockchain technology, smart contracts, and non-

fungible tokens (“NFTs”) can create faster, more

transparent royalty regulation and distribution for music

creators while improving the initiatives set forth in the

Music Modernization Act of 2018 (the “MMA”). No one

likes a broken record, but the music industry’s system for

royalty collection and distribution has been disjunct,

inefficient, and incomplete since the digitization of CDs

into MP3 files in the 1990s. There have only been

retroactive fixes to treat the symptoms of a broken system

with no proactive solutions to identify the cause of the

underlying issues and eradicate them. This article analyzes

the incomplete history of digitizing musical metadata and

highlights how vital comprehensive royalty regulation is to

creators by considering the ramifications unmatched and

unclaimed works have on these individuals. The article

proposes three initiatives to address the inconsistent

metadata standard currently disrupting digital music

consumption: (1) the creation of an MMA-specific

blockchain that provides uniform, transparent data

standards; (2) the implementation of smart contracts to

facilitate autonomous royalty distribution; and (3) the

utilization of NFTs to connect smart contract functionality

with blockchain’s uniformity.

I. Introduction ............................................................. 520

II. A [Tuning] Fork in the Road: Copyright Law, Music

Ownership, and Royalty Regulation ............................... 526

A. Musical Copyrights—Musical Composition and

Sound Recording ......................................................... 526

B. Music Industry Entity Breakdown ...................... 530

520 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

III. Addressing the Music Industry’s Biggest Broken

[Data] Record: Inconsistent Music Metadata Standards and

Lack of Comprehensive Database .................................. 532

A. Musical Mediums—Records to CDs to MP3s .... 532

B. Broken [Metadata] Records and Copyright

Ownership ................................................................... 536

IV. An Unmatched Solution to the Music Industry’s

Unmatched Royalty Problem: How Blockchain, Smart

Contracts, and NFTs can Revolutionize Royalty Regulation

and Distribution .............................................................. 538

A. A Universal Database with a Uniform Standard—

The MLC Blockchain ................................................. 538

B. Consistent, Automatic Royalty Distribution—Smart

Contracts ..................................................................... 547

C. Music Mediums Revisited—CDs to MP3s to

NFTs ........................................................................... 549

V. Conclusion .............................................................. 552

I. INTRODUCTION

A customer enters a bakery and orders a chocolate

chip cookie. The customer eats the cookie and then tells

the baker they will pay for the cookie . . . in six months.

The discrepancy here, between when the customer eats the

cookie and when the baker is paid, is objectively

unacceptable. Society would never let this type of behavior

go unadmonished. However, if two substitutes are made to

this example—a musical composition replaces the cookie,

and a songwriter replaces the baker—the crippling

implications of prolonged music royalty distribution on a

songwriter’s career become evident.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 521

Volume 63 – Number 3

The most important component of the music

industry has always been creators. Songwriters create

recipes that record labels use to create wonderful dishes

that an unlimited number of people can sample. These

individuals rely on accurate data transfer—how frequently

a song has been played—to receive proper royalty

compensation. However, each entity involved in today’s

music royalty distribution process stores song data

differently. These database discrepancies create

incomplete, inconsistent data entries that result in lost

wages, data duplication, and unmatched or unclaimed

works.

1

Inaccurate data not only leads to songwriters not

getting paid but also to songwriters not receiving credit and

recognition for their talents. In an industry founded on

creative collaborations and networking, not giving credit to

the proper individuals can have a devastating impact on a

creator’s career.

2

New leaps in technology, like smart contracts and

non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) housed on blockchains, can

make the music royalty distribution process more

transparent and the data collection governing music

copyright ownership more reliable and immune to

manipulation and delays.

3

Royalty allocation is dependent

1

Unclaimed works refer to inadequate information regarding

the writer’s and the publisher’s shares in a composition. See U.S.

COPYRIGHT OFF., UNCLAIMED ROYALTIES: BEST PRACTICES FOR THE

MECHANICAL LICENSING COLLECTIVE 43 (2021), https://www.copy

right.gov/policy/unclaimed-royalties/unclaimed-royalties-final-report.p

df [https://perma.cc/9THL-NU4R]. Thus, every time a master

recording is played, the songwriters and publisher will not receive

compensation. See Frequently Asked Questions, THE MLC,

https://www.themlc.com/faqs/categories/mlc [https://perma.cc/7B2Q-

Y3GQ] (last visited Mar. 23, 2023). Unmatched recordings implicate

the recording artist and record label. See id.

2

Catherine L. Fisk, Credit Where It’s Due: The Law and

Norms of Attribution, 95 GEO. L.J. 49, 76 (2006).

3

See infra Section IV (discussing NFTs and smart contracts).

522 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

on accurate information being available, but the current

system lacks a uniform data standard, resulting in a slow,

and at times incomplete, compensation process.

4

Congress attempted to address these issues by

enacting the Music Modernization Act of 2018 (the

“MMA”).

5

The MMA offered a more efficient way for

streaming services to pay for music rights by creating a

blanket mechanical license that granted specific, limited

protections to streaming services playing full catalogs of

music provided by distributors and record labels.

6

In July

2019, the U.S. Register of Copyrights designated the

Mechanical Licensing Collective (the “MLC”) to simplify

the mechanical royalty regulation process and make

copyright ownership data more transparent.

7

A Board of

Directors—comprised of ten music publishers and four

professional songwriters—make up the MLC governance

structure.

8

Three Advisory Committees (the

4

See Leticia Trandafir, Everything Musicians Need to Know

about Music Distribution, LANDR BLOG (Jan. 12, 2021),

https://blog.landr.com/everything-musicians-need-know-digital-music-

distribution/ [https://perma.cc/22Y2-T84Q] (providing an in-depth

discussion on the music creation and distribution process); see also

infra note 21.

5

Orrin G. Hatch-Bob Goodlatte Music Modernization Act of

2018, Pub. L. No. 115-264, 132 Stat. 3676 (2018) (codified as amended

at 17 U.S.C. § 101).

6

Governance and Bylaws, THE MLC,

https://www.themlc.com/governance [https://perma.cc/9L73-EB42]

(last visited Mar. 23, 2023); see also Frequently Asked Questions,

supra note 1.

7

See Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1.

8

Governance and Bylaws, supra note 6 (“[The MLC] is led by

a Board of Directors that is comprised of fourteen individuals: ten must

be representatives of music publishers and four must be professional

songwriters who retain and license mechanical rights for songs they

have written. No two Directors may be affiliated with music publishers

under common control or ownership. There are also three nonvoting

Directors representing trade organizations for songwriters, music

publishers, and digital music providers, respectively.”).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 523

Volume 63 – Number 3

“Committees”) aid the MLC’s Board of Directors in

executing its objectives: the Unclaimed Royalties Oversight

Committee,

9

the Dispute Resolution Committee,

10

and the

Operations Advisory Committee.

11

These Committees help

serve the MLC’s “purposes, operations, or other activities

or topics,” but their exact roles are not clearly defined in

the current MLC bylaws.

12

When the MLC became the

exclusive administrator of the MMA’s blanket license

program, it was tasked with collecting royalties owed by

the streaming services and distributing those royalties to the

correct rightsholders.

13

The MLC also created a public database of musical

works, sound recordings, and copyright owners, hoping to

fix a system that had generated $2.5 billion in unclaimed

royalties by making copyright ownership information more

transparent and accessible to the public.

14

However, after

9

This committee is composed of five songwriters and five

music publishing representatives. Id.

10

This committee is composed of five songwriters and five

music publishing representatives. Id.

11

This committee is composed of six music publishing

representatives and six digital music provider representatives. Id.

12

See THE MLC, BYLAWS OF THE MECHANICAL LICENSING

COLLECTIVE 13 (2020), https://f.hubspotusercontent40.net/hubfs/871

8396/files/2020-05/Bylaws%20of%20The%20MLC.pdf [https://perma

.cc/SW7W-98YY].

13

A blanket license is issued by a collection society allowing a

user to play and/or perform all compositions or recordings managed by

all publishers represented by that group. Blanket License, SONGTRUST,

https://www.songtrust.com/music-publishing-glossary/glossary-blanket

-license [https://perma.cc/Q6XW-LQBC] (last visited Mar. 23, 2023);

THE MLC, 2021 ANNUAL REPORT 1 (2021), https://www.themlc.

com/hubfs/Marketing/23856%20The%20MLC%20AR2021%206-30%

20REFRESH%20COMBINED.pdf [https://perma.cc/BS5B-7DK4].

14

R.B. Jefferson, What Do the MMA and MLC mean for

Songwriters and Composers in 2021?, LAWYERS ROCK (Dec. 18,

2020), https://www.lawyersrock.com/what-do-the-mma-and-mlc-mean-

for-songwriters-and-composers- in-2021/ [https://perma.cc/X3CY-

524 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

the MLC distributed its first round of royalty payments in

2021, nearly half a billion dollars of unmatched royalties

remained.

15

While the MLC was a positive step toward

reliable digitization of the music royalty system, significant

gaps in accomplishing a cohesive data tracking protocol

remain. The MLC created a system to identify some

unclaimed works and regulate mechanical royalty

distribution, yet it failed to provide a proactive solution that

can minimize future unmatched works and does not address

the three other types of music royalties at all.

16

The MLC’s initiatives are an important step, but

they are not the solution that will get the industry to a

comprehensive music royalty distribution finish line.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in unmatched royalties are

still held by the MLC, and the number is set to grow as the

process of matching royalties to artists remains slow and

arduous.

17

Blockchain technology, smart contracts, and

NFTs can be implemented to streamline the music royalty

distribution system. Smart contracts would track copyright

RZF9]. The MLC also implemented a system called SoundExchange

to track satellite and digital radio logs. Id. SoundExchange is a state-

of-the-art music fingerprinting technology that records radio broadcasts

and then cross-checks those streams with a database of 68 million

songs to record public performance royalties. Who We Are,

SOUNDEXCHANGE, https://www.soundexchange.com/who-we-are/ [htt

ps://perma.cc/XN87-9UTX] (last visited Dec. 13, 2022).

15

The exact value of unmatched royalties remaining is

$424,384,787. LB Cantrell, The MLC Receives $424 Million In

Historical Unmatched Royalties From DSPs, MUSICROW (Feb. 16,

2021), https://musicrow.com/2021/02/the-mlc-receives-424-million-in-

historical-unmatched-royalties-from-dsps/ [https://perma.cc/FY59-ZW

CE]; see infra notes 41–46 and accompanying text (discussing the

cause of accrued historical unmatched royalties).

16

See infra note 21 (discussing public performance royalties,

synchronization royalties, and print music royalties).

17

In the current system, a creator must wait months to receive

compensation. See infra Section II(B) (providing additional

information regarding the specific entities involved in this process).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 525

Volume 63 – Number 3

ownership information while NFTs would store song

metadata, and both would be recorded and tracked on an

MLC-specific blockchain. Utilizing these innovative

methods, in conjunction with the MLC’s current initiatives,

would accomplish autonomous, transparent, and

instantaneous royalty distribution.

Section II of this article establishes the two types of

musical copyrights—musical compositions and sound

recordings—and silos the music industry’s entities into

three categories: music-creation entities, business

intermediaries, and customer-facing entities. Section III

explores the history of music royalty regulation and

identifies the main issue keeping the current system from

functioning efficiently: inconsistent metadata tracking and

lack of a uniform database to house accurate data. Section

IV proposes a solution to this problem: an MLC-operated

blockchain that employs NFTs (tracking song metadata)

and smart contracts (tracking copyright ownership splits) to

facilitate smart royalty distributions. Finally, Section V

summarizes the benefits of the proposed solutions and

argues that utilizing blockchain technology, smart

contracts, and NFTs would fulfil the MLC’s purpose to

simplify the royalty regulation process and make copyright

ownership transparent for all users.

18

18

The Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC), COPYRIGHT

ALLIANCE, https://copyrightalliance.org/trending-topics/mechanical-lic

ensing-collective/ [https://perma.cc/D7QW-CFN9] (last visited Mar.

23, 2023) (“The MLC’s mission is to ensure that songwriters,

composers, lyricists, and music publishers receive accurate and timely

mechanical license royalty payments from streaming and download

services across the U.S. To fulfill this goal, the MLC built a publicly

accessible musical works database, along with a portal that creators and

music publishers can use to submit and maintain their musical works

data. It also developed a number of other related tools to ensure that

the process of registering with the MLC (and tracking royalties through

it) is a smooth and seamless process.”).

526 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

II. A [TUNING] FORK IN THE ROAD: COPYRIGHT

LAW, MUSIC OWNERSHIP, AND ROYALTY

REGULATION

A. Musical Copyrights—Musical Composition

and Sound Recording

Every song has two copyrightable layers—a

musical composition and a sound recording.

19

Musical

compositions are the totality of underlying notes, lyrics,

and melody that make up a song.

20

Musical compositions

create publishing rights that result in public performance

royalties paid to the creator and their publisher.

21

A sound

19

U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., COMPENDIUM OF U.S. COPYRIGHT

OFFICE PRACTICES § 802.2(B) (3d ed. 2021), https://www.copyright.

gov/comp3/docs/compendium.pdf [https://perma.cc/62E8-RJQW].

20

Id.; see also Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1

(“Sometimes referred to as a composition or song, a musical work

consists of music, including any accompanying lyrics.”).

21

There are four music royalties: public performance

royalties, mechanical royalties, synchronization royalties, and print

music royalties. Rory PQ, How Music Royalties Work in the Music

Industry, ICON COLLECTIVE (Mar. 30, 2020), https://iconcollective.edu/

how-music-royalties-work/ [https://perma.cc/SRQ9-7KFL]; see also

Dmitry Pastukhov, How Does the Music Industry Work? Introducing

the Mechanics: A 10 Part Series, SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (Jan. 7, 2019)

[hereinafter Pastukhov, Music Industry], https://soundcharts.com/

blog/mechanics-of-the-music-industry [https://perma.cc/9XWC-RJN2].

Synchronization and print music royalties will not be discussed in this

paper, but they are key components of the music royalty equation.

Dmitry Pastukhov, BMI vs ASCAP vs SESAC: What PROs Do (and

How They Measure Up), SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (Feb. 18, 2020)

[hereinafter Pastukhov, PROs], https://soundcharts.com/blog/bmi-vs-

ascap [https://perma.cc/JL6E-3QUM]. Synchronization royalties result

from synchronizing (“pairing”) a specific song with some form of

visual media. PQ, supra. These types of royalties are managed by

artists and their managers or labels. For example, while it costs the

same to play a Taylor Swift song and a new artist’s song on the radio or

on a streaming service, using a Taylor Swift song in an advertisement

will cost you millions more than using an unknown artist’s work.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 527

Volume 63 – Number 3

recording is the song that results from a musical

composition.

22

Sound recordings create master rights that

result in mechanical royalties paid to the record label and

the recording artist.

23

Currently, no uniform standard exists

to link a musical composition and its sound recordings.

While musical composition data is tracked using one

system,

24

sound recording data is tracked using another.

25

Dmitry Pastukhov, Music Publishing 101: Copyrights, Publishing,

Royalties, Common Deal Types, & More, SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (Nov.

20, 2019) [hereinafter Pastukhov, Music Publishing 101], https://sound

charts.com/blog/how-the-music-publishing-works [https://perma.cc/7F

H9-HVBC]. Additionally, both the composition and sound recording

owners must agree to the use and the resulting royalty is shared

between the recording and publishing sides. Id. Printed music

royalties are much less common in the digital age. PQ, supra. The

number of sheet music copies physically made determines the amount

of royalties the copyright holder will receive. Id.

22

17 U.S.C. § 101. Sound recordings and their rights typically

belong to the owner of the “master” and are key in reproduction and

distribution uses. PQ, supra note 21. Historically, record labels have

held master rights because they are the ones paying for the studio time

that the recording artist uses to create the sound recording. See id.

23

Master rights attach to a specific sound recording. See

Pastukhov, Music Publishing 101, supra note 21. Labels then use

contracts to leverage the recordings of their artists in return for royalty

payments over a specific period, while a recording artists signed to the

label will receive a flat rate or percent of the mechanical royalties that

result. See id. Even though record label frequently own the master

rights to a sound recording, they cannot own the publishing rights in

the composition. Id.

24

An International Standard Music Code (“ISWC code”)

tracks musical compositions. ISWC NETWORK, https://www.iswc.org/

[https://perma.cc/WEN3-LBYR] (last visited Apr. 24, 2023);

International Standard Music Code, WIKIPEDIA, https://en.wikipe

dia.org/wiki/International_Standard_Musical_Work_Code [https://per

ma.cc/DX9T-DANB] (last visited Mar. 23, 2023); see also Peter

Schneider, What Are ISWC/ISRC Codes and How do I Get Them?,

SONGTRADR (Sept. 6, 2016), https://blog.songtradr.com/what-are-iswc-

isrc-codes-and-how-do-i-get-them/ [https://perma.cc/6QA2-AQXN].

ISWCs are unique codes assigned to a specific musical composition

528 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

The critical information within the composition and

sound recording metadata ensure that contributing parties

receive payment when songs are played. Slow, incomplete

royalty distribution will continue without a consistent data

standard and a central location to find all copyright

ownership information.

26

Additionally, discrepancies in

allowing for easy identification within recordings and proper royalty

distribution. Id. These codes track the song title, songwriter(s), music

publisher(s), and the ownership/publisher shares in the piece. Id.

25

An International Standard Recording Code (“ISRC code”)

tracks sound recordings. ISRC, http://usisrc.org/ [https://perma.cc/

U5BA-S94A] (last visited Apr. 24, 2023); International Standard

Recording Code, WIKIPEDIA, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internat

ional_Standard_Recording_Code [https://perma.cc/QZR2-JCP6] (last

visited Mar. 23, 2023). To create an ISRC code, an artist must pay $80.

See Schneider, supra note 24. The standard for music identification

across all entities is to track the sound recording code but not the music

composition code. See Dmitry Pastukhov, How Broken Metadata

Affects the Music Industry (And What We Can Do About It)?,

SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (July 15, 2019), https://soundcharts.com/blog/

music-metadata [https://perma.cc/KA23-AVJ3]; see also Henry

Schoonmaker, What’s the Difference Between ISRCs and ISWCs?,

SONGTRUST (Apr. 6, 2020), https://blog.songtrust.com/isrc-iswc-song-

registration-tips [https://perma.cc/K2ZH-VLAA] (“Publishers,

collection societies, record labels, distributors, and [DSPs] use ISRCs

to match master recordings to . . . compositions.”). The MLC has also

created its own tracking system for the works in its database—MLC

Song Codes. See The MLC Public Work Search, THE MLC,

https://portal.themlc.com/search#work [https://perma.cc/9WBB-94HY]

(last visited Apr. 24, 2023) (allowing a user to search by MLC song

code).

26

While the ISWC works with 54 registration agencies across

79 countries to issue ISWC codes to musical compositions, the current

system has only registered and assigned codes to 52 million works. See

A Unique Identifier of Musical Works Across the World, ISWC

NETWORK, https://www.iswc.org/ [https://perma.cc/X4LK-573C] (last

visited Mar. 23, 2023). It is estimated there are at least 97 million

songs in the world. Brian Clark, How Many Songs are There in the

World? (2022), MUSICIANWAVE (Apr. 28, 2022), https://www.

musicianwave.com/how-many-songs-are-there-in-the-world/ [https://p

erma.cc/6T3B-UV4Q] (“Considering the fact that the web has about 97

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 529

Volume 63 – Number 3

ownership data can lead to the creation of unmatched

recordings or unclaimed works.

27

When a sound

recording’s data is not adequately matched to its underlying

musical work, an unmatched recording results.

28

Unmatched royalties implicate the recording artist and the

record label.

29

Unclaimed works result when less than

100% of a musical work’s ownership shares have been

claimed.

30

Thus, every time a sound recording with

inadequate data is played, the songwriter and/or publisher

will not receive proper compensation because either the

musical work is not connected to the sound recording, or

the initial data about ownership in the musical work was

not allocated properly.

million songs on average shown by Google, while Spotify states they

have 82 million, it is safe to assume that music only continues to

grow.”). Thus, nearly half of the compositions and sound recordings

that result are not currently accounted for or adequately tracked. See

id.

27

See Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1.

28

Id.

29

See U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., supra note 1, at 28. (“Other

commenters stated that certain songwriters may not have ‘heard of a

PRO or . . . publisher,’ know about standard unique identifiers (e.g.,

ISWCs or ISRCs), understand the roles of PROs versus U.S.

government-designated collectives (SoundExchange and the MLC), or

know that they do not need to be signed to a record label or publishing

company to participate in royalty collection and distribution systems.”)

(internal citations omitted).

30

Id. (“For example, if only 80% of a musical work has been

claimed, the remaining 20% is unclaimed, and the royalties associated

with the unclaimed shares are referred to as unclaimed royalties.”).

530 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

B. Music Industry Entity Breakdown

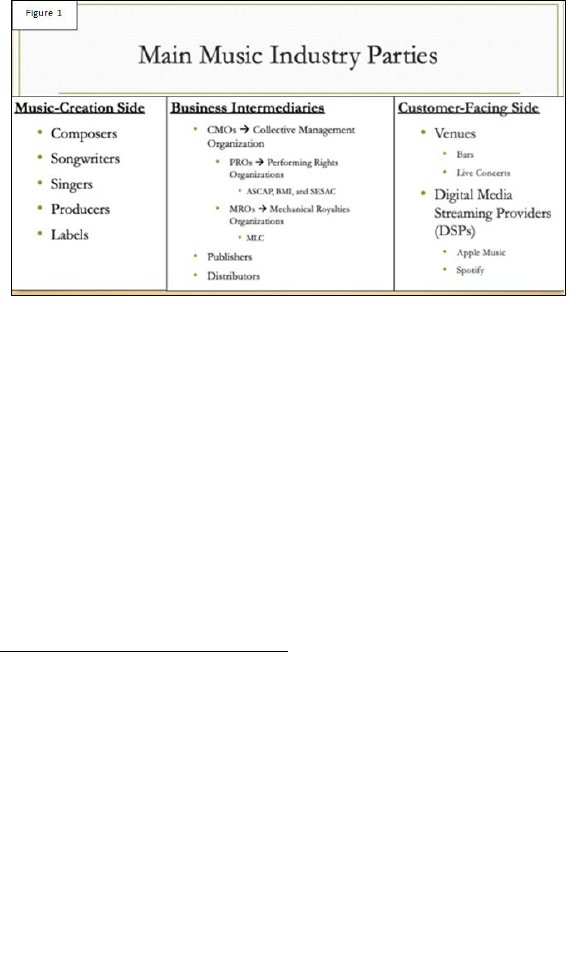

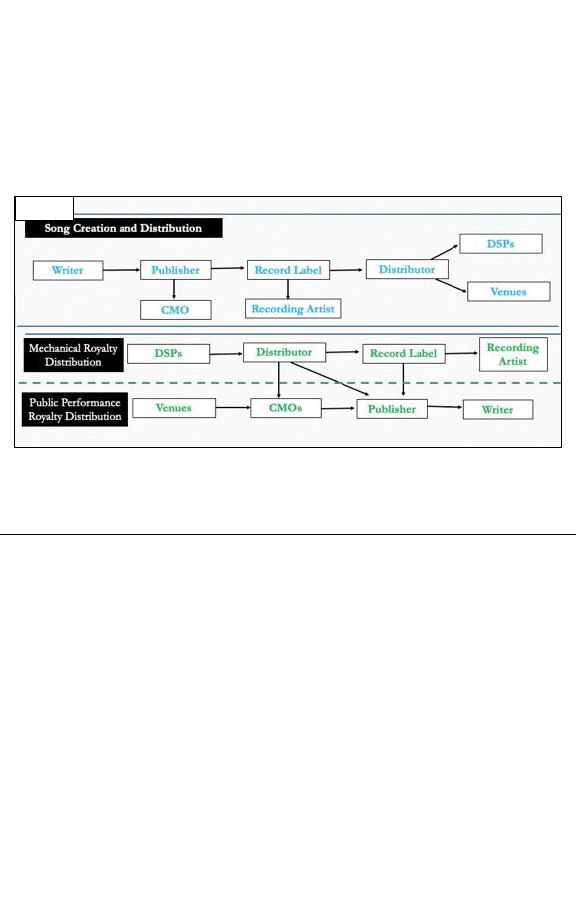

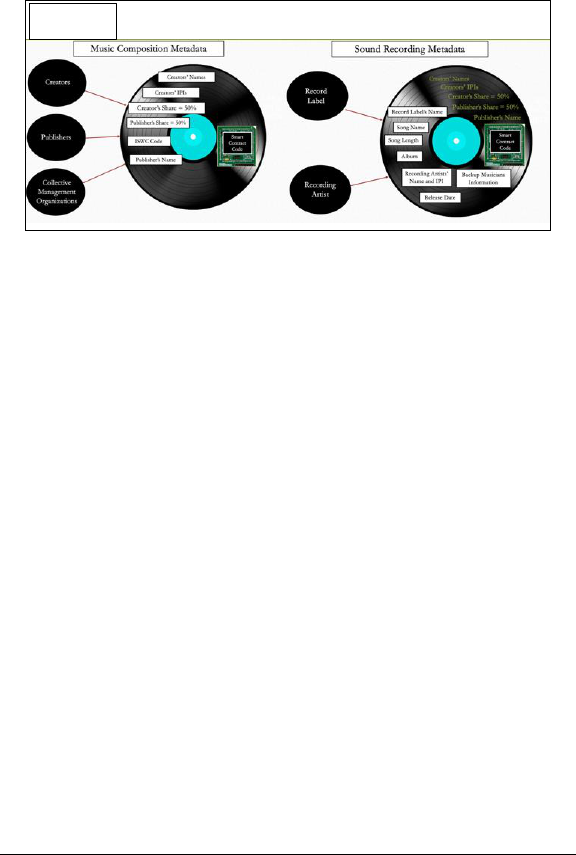

The music industry can be grouped into the three

silos shown in Figure 1: the music-creation entities, the

business intermediaries, and the customer-facing entities.

On the music creation side, singers, songwriters, and

musicians create the composition.

31

There are also

producers, record labels, and recording artists who turn that

composition into a sound recording.

32

The business

intermediaries are distributors, streaming services,

collective rights organizations, and publishers. Distributors

are a bridge between streaming services and labels.

33

Publishers work with songwriters to register a composition

31

See id.

32

See PQ, supra note 21.

33

Distributors get music in front of the right listeners, on the

right platforms, at the right time and ensure royalties are delivered to

the copyright owners by condensing the customer-facing entity

information into manageable royalty allocation data. See Pastukhov,

Music Publishing 101, supra note 21. Distributors are a crucial part of

the recording chain with three key roles: distribute releases to DSPs,

allocate royalties appropriately, and create a marketing approach for

specific songs or clients. Id. Music distributors are now digital

infrastructure providers and rights administrators rather than just supply

chain managers. Id. They use their power as “bulk representatives” to

negotiate deals most favorable to the artists they represent. Id.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 531

Volume 63 – Number 3

with a collective rights organization and use licensing fees

to make sure writers get paid.

34

Collective rights

organizations track, collect, and distribute royalties owed to

artists and creators.

35

Finally, there are customer-facing

entities. Venues generate and pay public performance

royalties for the public use of a song.

36

Streaming services

generate mechanical royalties from the streaming of a song

34

Publishers bring compositions to record labels who might

produce the work into a sound recording. Id. Music publishers can

obtain a license to use the songwriting copyright in exchange for

royalty privileges. Id. Publishers are crucial for songwriters and

producers who write songs for other artists as these individuals’ focus

is on the success of the underlying work and not the resulting sound

recording. Id.

35

Mechanical Royalty Organizations (“MROs”) collect

mechanical royalties and issue rights to anyone reproducing or

distributing copyrighted musical compositions. Music Publishing

Glossary: Mechanical Royalty Organizations (“MROs”), SONGTRUST,

https://www.songtrust.com/music-publishing-glossary/glossary-mechan

ical-rights-organization [https://perma.cc/4BTW-9FML] (last visited

Mar. 24, 2023). The Harry Fox Agency or the Mechanical Licensing

Committee (the “MLC”) established under the MMA are examples of

MROs. Performing Rights Organizations (“PROs”) license an artist’s

rights to music users, monitor the use, and collect the resulting public

performance royalties. Diana Akin Scarfo, Music Publishing 101:

What’s a Performance Rights Organization (PRO)?, REVERBNATION

BLOG (Aug. 29, 2016), https://blog.reverbnation.com/2016/08/29/music

-publishing-101-whats-a-performance-rights-organization-pro/ [https://

perma.cc/8SL5-73CK]. The three main PROs in the United States are

American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (“ASCAP”),

Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”), and Society of European Stage Authors

and Composers (“SESAC”). See Pastukhov, PROs, supra note 21.

PROs rely on metadata logged by DSPs, radio stations, and other

public performance venues to determine the royalty rates and payout

amounts for each artist. Id.

36

An example of a venue is a bar, restaurant, concert hall,

radio station, or other location where you hear music.

532 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

and must distribute the collected royalties to the proper

parties.

37

III. ADDRESSING THE MUSIC INDUSTRY’S BIGGEST

BROKEN [DATA] RECORD: INCONSISTENT MUSIC

METADATA STANDARDS AND LACK OF

COMPREHENSIVE DATABASE

A. Musical Mediums—Records to CDs to

MP3s

The initial digital music data collection method had

major flaws.

38

When CDs were introduced in 1980, they

37

Streaming services, often referred to as Digital Service

Providers (“DSPs”), are entities like Apple Music or Spotify.

Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1. While venues are just

responsible for reporting public performance royalties, DSPs must track

and distribute three different types of payments to copyright owners:

(1) mechanical royalties to the recording artist and record label from all

specific streams from a song; (2) public performance royalties paid to

the songwriter and the publisher for every public performance that

occurs; and (3) payment to recording owners such as labels or

distributors. What Music Streaming Services Pay Per Stream (And

Why It Actually Doesn’t Matter), SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (June 26, 2019),

https://soundcharts.com/blog/music-streaming-rates-payouts [https://p

erma.cc/6VAV-8UWG]. Each group is made up of many individuals.

For brevity, these groups will be referenced broadly when applicable.

38

See Ryan Waniata, The Life and Times of the Late, Great

CD, DIGITALTRENDS (Feb. 7, 2018), https://www.digitaltrends.com/

music/the-history-of-the-cds-rise-and-fall/ [https://perma.cc/FL6Y-C3J

A] (“While CDs have been on their way out for some time now, this

week’s news may as well be a eulogy or the once-mighty disc,

signaling a last step in its passing from a dominant medium to a

forgotten relic in the ever-changing pantheon of recorded music.”); see

also Anne S. Huffman, Note, What the Music Modernization Act

Missed, and Why Taylor Swift Has the Answer: Payments in Streaming

Companies’ Stock should be Dispersed Among all the Artists at the

Label, 45 IOWA J. CORP. L. 537, 538, 546–47 (2020) (recommending

that record labels and artists find contractual solutions to ensure artists

are being paid adequately for their work).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 533

Volume 63 – Number 3

had minimal space to store data, so only basic song

information was tracked on the actual disk.

39

Thus, when

CDs started to be digitized into MP3 files in the late 1990s,

minimal data was available to upload.

40

Unfortunately,

there was no uniform data collection process during this

period, so dozens of databases with differing standards

resulted.

41

This lack of standardization meant that the

early-2000s digital music databases lacked key information

about the underlying rights in the songs they were

distributing. These factors built a digital universe of poorly

archived MP3 files on a foundation of inconsistent data that

continues today.

42

Despite the massive evolution of technology since

MP3 files were introduced, the incompatible metadata

standards have never been fixed. Most musical databases

still vary significantly in how they store copyright data

making the transfer between parties inefficient and

sometimes impossible. The industry is essentially playing

a game of telephone, attempting to translate data that is not

compatible from one entity to another. Inconsistent data

39

The case and lyric pamphlet that accompanied the CD

carried more specific data regarding specific publishers, recording

label, songwriters, etc. See generally Spencer Paveck, Note, All the

Bells and Whistles, but the Same Old Song and Dance: A Detailed

Critique of Title 1 of the Music Modernization Act, 19 VA. SPORTS &

ENT. L.J. 74 (2019) (discussing a detailed history of the music

industry’s adaption to the rapidly-changing digital environment); Jillian

J. Dahrooge, Note, The Real Slim Shady: How Spotify and Other Music

Streaming Services Are Taking Advantage of The Loopholes Within the

Music Modernization Act, 21 J. HIGH TECH. L. 199 (2021).

40

Waniata, supra note 38.

41

See Pastukhov, supra note 25 (“Imagine that a database

receives a value in the field ‘Back Vocalist’—when its own

corresponding column is called ‘Back Vocals.’ Algorithms won’t be

able to make that match (unless there’s a specific rule for it) and in

99% of the cases, the back vocalist’s credit will just get scraped. A big

chunk of metadata gets lost on its way through the music data chain.”).

42

Id.

534 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

standards and the lack of a uniform database to track song

information and engagement create a substantial lag

between when a song gets played and when the creator gets

paid, typically between three months and a year depending

on the entities involved.

43

Compounding the technical translation delays is the

lack of incentive for business intermediaries to relay

collected royalties to the creators, because if the money

remains unclaimed, the default is that these entities keep

it.

44

The MMA attempted to address this disconnect by

43

Seth Lorinczi, Publishing Royalties: The Waiting Game,

SONGTRUST (Aug. 1, 2019), https://blog.songtrust.com/music-

publishing-royalties-the-waiting-game [https://perma.cc/Q2WU-WXW

J]. ASCAP has an average payout to publishers, and by extension its

artists, of 6.5 months. Id.; see supra note 35 (defining ASCAP). BMI

has an average payout of 5.5 months. How We Pay Royalties, BMI,

https://www.bmi.com/creators/royalty/general_information [https://per

ma.cc/6NBL-9JHK] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023); see supra note 35

(defining BMI). ASCAP collects metadata about work registration

such as title, writer, and/or publisher. It also uses a complex credit

system to determine how much each party receives in royalties (credits

× share × credit value = royalty). How ASCAP Calculates Royalties,

ASCAP, https://www.ascap.com/help/royalties-and-payment/payment/

royalties [https://perma.cc/4EXM-94YQ] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023);

see also Turning Performances Into Dollars, ASCAP,

https://www.ascap.com/help/royalties-and-payment/payment/dollars [ht

tps://perma.cc/QK54-39YD] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023). ASCAP

employs a census versus sample survey approach, meaning it

unintentionally discounts the artist’s actual royalty realization because

it is not economically beneficial for ASCAP to perform a census for a

certain song or genre. See The ASCAP Surveys, ASCAP,

https://www.ascap.com/help/royalties-and-payment/payment/surveys

[https://perma.cc/3QDD-HAVD] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023). As a

result, the artist will get incorrect royalties based on a sample rather

than actual plays of their work. Id.; see also Keeping Track of

Performances, ASCAP, https://www.ascap.com/help/royalties-and-

payment/payment/keepingtrack [https://perma.cc/S5JZ-62HU] (last

visited Mar. 24, 2023).

44

Chris Castle, Best Practices for Unmatched Royalties,

MUSIC TECH. POL’Y BLOG (June 24, 2014), https://musictechpolicy

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 535

Volume 63 – Number 3

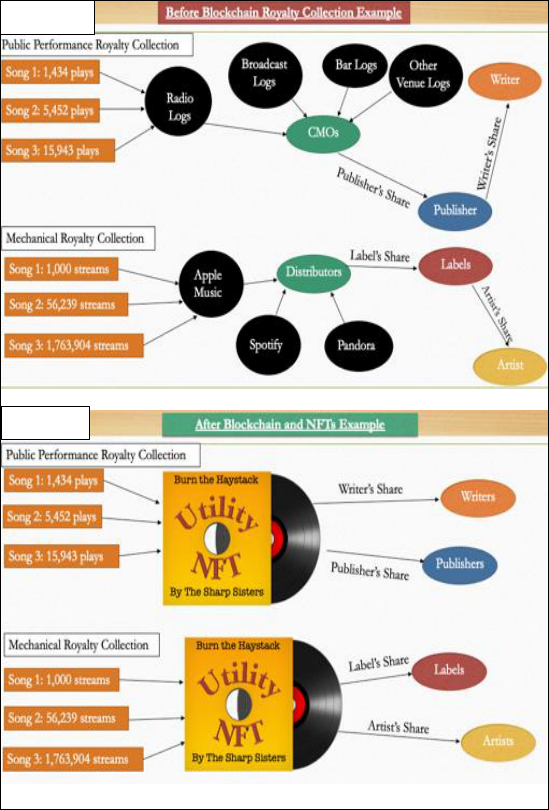

Figure 2

allowing streaming services to avoid some future liability if

they turned over all unpaid, unclaimed royalties that had

accrued through 2018.

45

However, under the current

system, distributors still remain an unnecessary bridge

collecting and relaying royalties between streaming

services and record labels, while publishers do the same

between the collective rights organizations and the actual

creators, as seen in Figure 2.

46

.com/2014/06/24/best-practices-for-unmatched-royalties/ [https://perma

.cc/6Z8P-687V] (“We should not be surprised that services have a great

incentive to sit on the songwriter’s money and not spend any additional

efforts to find the songwriters.”).

45

20 DSPs transferred accrued historical unmatched royalties

to the MLC. The Mechanical Licensing Collective Receives $424

Million in Historical Unmatched Royalties from Digital Service

Providers, THE MLC (Feb. 16, 2021), https://blog.themlc.com/press/

mechanical-licensing-collective-receives-424-million-historical-unmatc

hed-royalties-digital [https://perma.cc/TX6E-W9QL].

46

Since April 2016, there have been over 46 million cases

filed with the United States Copyright Office involving unidentified

songwriters. Asaf Deke, Data Has A Lot To Say About Music

Royalties, All You Need To Do Is Listen, BRIGHT DATA,

https://brightdata.com/blog/brightdata-in-practice/data-and-music-royal

ties [https://perma.cc/3BJD-CXGV] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023).

536 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

B. Broken [Metadata] Records and Copyright

Ownership

There are two types of metadata required to create a

comprehensive music database: ownership metadata and

description metadata.

47

Ownership metadata ensures

correct royalty allocation occurs by tracking the

percentages owed to each music-creation entity involved in

a composition’s creation. Errors in this type of data are

devastating to creators as they lose both monetary

compensation and credit.

48

Descriptive metadata tracks

details about a specific sound recording.

49

Errors in this

data result in misspelled song names, mixed up release

47

Pastukhov, supra note 25.

48

Id. In fact, this type of data is often called “artist credits”

because it is a crucial way for an individual artist to gain traction and

notoriety within the industry. See id. One way to ensure artists are

protected has been the creation and implementation of songwriter split

sheets. Rory PQ, Everything You Need to Know about a Split Sheet,

ICON COLLECTIVE (May 4, 2020), https://iconcollective.edu/songwriter-

split-sheet/ [https://perma.cc/Z28U-UFX8]. The default for these

agreements is that ownership of a co-written work will be equally

divided among the contributors unless a split sheet is agreed upon. Id.

This default helps circumvent legal headache by requiring all

contributors to sit down and determine, in writing, what the ownership

split will be from the outset. Id. Without a split sheet, contributors risk

never getting paid or receiving credit for their input because PROs will

not know who to pay. Id. A split sheet must include the date, song

title, legal names of all contributing writers involved, role in the song

creation (producer, songwriter, etc.), ownership percentage for each

contributor, specific contributions (lyrics, hook, melody, beats, etc.),

record label (if applicable), PRO (if applicable), publishing company (if

applicable), mailing addresses and contact information for contributing

parties, and written signature of each contributor. Id.

49

Pastukhov, supra note 25. Description metadata collects

information about song title, release date, track number, performing

artist, cover art, and main genre. Id.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 537

Volume 63 – Number 3

dates, and other inadequacies that create unmatched works

or delayed royalty distribution.

50

However, despite the 2018 enactment of the MMA

and the MLC, there has been no attempt at music data

standardization even though the MLC’s own website states

“[t]he MLC has the support of organizations from every

corner of the music industry.”

51

The MLC acknowledges

that “record companies are not required to directly deliver

their sound recording data to the MLC,” and without a

uniform system in place requiring all parties to use a

consistent standard, data discrepancies and prolonged

royalty distribution will persist.

52

If the music industry

continues to store metadata with different standards, the

difficulty in relaying information between business

intermediaries and customer-facing entities will remain

while making engagement with the information virtually

impossible for creators.

53

How can the industry implement

uniform data standards in a way that also streamlines

royalty distribution, provides more protection for creators,

and eradicates unmatched, or unclaimed works? The

answer: blockchain, smart contracts, and NFTs.

50

Id.

51

Governance and Bylaws, supra note 6.

52

Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1.

53

The Mechanics of Music Distribution: How it Works, Types

of Music Distribution Companies + 35 Top Distributors,

SOUNDCHARTS BLOG (June 29, 2022), https://soundcharts.com/

blog/music-distribution [https://perma.cc/5BHB-LRLA]. Creators

suffer the most harm under the current system. Streaming services add

to this problem by not allowing direct music uploads, requiring creators

to engage with distributors to help get their songs heard. Id. The

reason behind the apparent lack of artist autonomy is credited to an

“unstandardized metadata and payout distribution” system making

individual artist input impossible. Id.

538 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

IV. AN UNMATCHED SOLUTION TO THE MUSIC

INDUSTRY’S UNMATCHED ROYALTY PROBLEM:

HOW BLOCKCHAIN, SMART CONTRACTS, AND

NFTS CAN REVOLUTIONIZE ROYALTY

REGULATION AND DISTRIBUTION

A. A Universal Database with a Uniform

Standard—The MLC Blockchain

The MLC’s purpose is to ensure the public has

access and ownership over the songs that support the music

industry, but the MLC’s official website states that it “does

not have any current plans to incorporate blockchain

technology into its systems.”

54

However, while it is still in

its infancy, blockchain, smart contracts, and NFTs can

track musical metadata, aiding the MLC in ensuring that

creators get paid faster while optimizing data collection

through a uniform standard.

55

A smart digital royalty

system would also save the industry time and money by

erasing the hours of labor currently spent tackling data

discrepancies.

Data errors within the music industry are

preventable but much too common. An MLC blockchain

54

Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 1 (“Will blockchain

be used in the management of The MLC data? The MLC does not have

any current plans to incorporate blockchain technology into the

systems.”).

55

Defining Blockchain and Digital Assets, DELOITTE,

https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/about-deloitte/solutions/blockch

ain-digital-assets-definition.html [https://perma.cc/HQ8S-4MGJ] (last

visited Apr. 26, 2023) (“A non-fungible token (NFT) is a unique,

cryptographic unit of data that exists on a distributed ledger and cannot

be replicated . . . [NFTs] can represent digital media or real-world,

tangible items like artwork and real estate, which makes buying,

selling, and trading them more efficient while reducing the probability

of fraud. NFTs can also represent things like identities, property rights,

or even a bundle of rights—all encoded into digital contracts or

attestations.”).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 539

Volume 63 – Number 3

would ensure musical metadata is tracked in one central

place using one uniform metadata standard.

56

Blockchains

are digital distributed ledgers that are transparent,

decentralized, and immutable.

57

Blockchains are

decentralized, so instead of storing all the information

related to a transfer within one central computer, a

blockchain network sends the information to multiple

computers across the blockchain.

58

On a decentralized

blockchain, the failure of one computer does not negatively

affect the system, because the other computers continue

56

This would create uniform standards for inputting data, filing

proofs and rollups, and approving validators to ensure accurate,

transparent data is being recorded to the blockchain. Sharding addresses

scalability issues (with so much data likely to be logged) while

decreasing environmental/economic burden on validators because it

only requires them to track and maintain certain subsets of the data on

the connecting chains, typically the root hash. Rafael Fuentes, What is

Sharding and How is it Helping Blockchain Protocols?, ROOTSTRAP

(Sept. 6, 2022), https://www.rootstrap.com/blog/what-is-sharding-and-

how-is-it-helping-blockchain-protocols/ [https://perma.cc/A5LJ-ZKW

3] (“Sharding is a process that divides the whole network of a

blockchain . . . into several smaller networks, referred to as ‘shards.’”).

ZK and optimism rollups are key to successful implementation of

sharding. Robert Stevens, What Are Rollups? ZK Rollups and

Optimistic Rollups Explained, COINDESK (Sept. 7, 2022, 10:25 AM),

https://www.coindesk.com/learn/what-are-rollups-zk-rollups-and-optim

istic-rollups-explained/ [https://perma.cc/P2S7-VAFR].

57

See Jacob Cass, 10+ Different Types of NFTs—Complete

List, JUST CREATIVE (July 26, 2022), https://justcreative.com/types-of-

nfts/#consortium-blockchains [https://perma.cc/D39R-ATW3].

Essentially, a blockchain is the digital version of printed transaction

receipts. See id.

58

What is Decentralization?, WE TEACH BLOCKCHAIN,

https://weteachblockchain.org/faq/what-is-decentralization/ [https://pe

rma.cc/GTP7-LZKT] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023); see NIAZ

CHOWDHURY, INSIDE BLOCKCHAIN, BITCOIN, AND CRYPTOCURRENCIES

13–14 (2020) (“There is no dependency on a single server; hence

blockchain does not have a central point of failure.”).

540 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

supporting it.

59

Decentralization ensures that information

used to trace transactions can be recovered by another

computer on the blockchain if one computer fails.

60

Blockchains are transparent, because all virtual asset

transactions are recorded and accessible to anyone with

internet access. Finally, the blockchain record’s

immutability ensures all on-chain NFTs are accounted for

upon transfer.

61

There are private, public, and consortium

blockchains; the type of blockchain impacts the three

features mentioned above.

62

Public blockchains come with

more security risks because they are truly decentralized so

anyone can access them, but private blockchains are not

truly decentralized as they are only open to specific

individuals vetted by those who run that blockchain.

63

Consortium blockchains are the best of both worlds.

64

They are managed by a limited number of individuals,

called validator nodes (“nodes”), but viewable to anyone

59

See Jimi S., Blockchain: What are nodes and masternodes?,

MEDIUM (Sept. 5, 2018), https://medium.com/coinmonks/blockchain-

what-is-a-node-or-masternode-and-what-does-it-do-4d9a4200938f [htt

ps://perma.cc/26KU-RPF6].

60

See John Evans, Blockchain Nodes: An In-Depth Guide,

NODES.COM, https://nodes.com/ [https://perma.cc/RA5Q-74WW] (last

visited Mar. 24, 2023).

61

See CRYPTO DUKEDOM, THE NFT REVOLUTION: MUSIC

EDITION 20–21 (2021); see infra note 68 (discussing on-chain versus

off-chain transactions).

62

Private, public, and consortium blockchains: The

differences explained, COINTELEGRAPH, https://cointelegraph.com/

explained/private-public-and-consortium-blockchains-the-differences-e

xplained/amp [https://perma.cc/M7XY-RWV6] (last visited Mar. 24,

2023).

63

Id.

64

Id. Access to the blockchain can be as broad or as limited

as the validator nodes want. Id.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 541

Volume 63 – Number 3

granted access.

65

A consortium blockchain would allow

the MLC and its Committees to oversee creation and

operation of the blockchain, while ensuring information

could only be added to the chain by private actors who had

a copyright interest in the work being logged (i.e., music

creators, publishers, record labels, and recording artists).

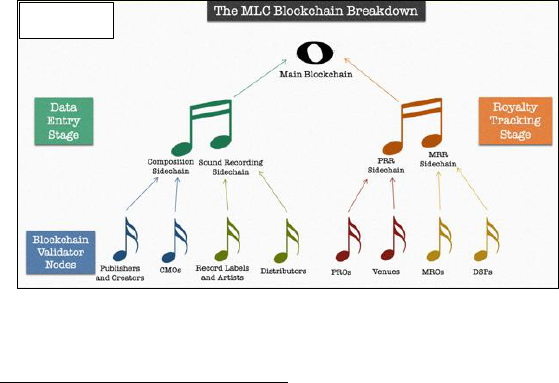

The main MLC blockchain, alongside four

sidechains discussed below, would track a summary of all

data from across the music industry and be governed by the

MLC and its Committees.

66

Blockchains often have

oracles—entities that transfer real-world data onto the

blockchain—and the MLC itself would be the main oracle

in this system.

67

It would screen music-creation entities,

65

See Jimi S., supra note 59. Validator nodes are authorities

on the blockchain that can submit data for consideration to be entered

on the chain. Id.; see CHOWDHURY, supra note 58, at 18 (“A

fundamental problem in distributed systems is achieving overall system

reliability in the presence of some faulty nodes . . . . Blockchain being a

distributed system requires its nodes to reach a consensus while

running the system and keeping its data secure.”).

66

See Governance and Bylaws, supra note 6; see also supra

notes 8–12 and accompanying text (discussing advisory committees).

67

See What is a blockchain oracle, and how does it work?,

COINTELEGRAPH, https://cointelegraph.com/blockchain-for-beginners/

what-is-a-blockchain-oracle-and-how-does-it-work [https://perma.cc/D

S3Y-XP3N] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023). While Proof of Work and

Proof of Stake are the most common blockchain consensus methods,

the blockchain argued for in this paper would use a Proof of Authority

(“PoA”) consensus method. Simon Chandler, Proof of stake vs. proof

of work: key differences between these methods of verifying

cryptocurrency transactions, BUS. INSIDER (Nov. 21, 2022, 1:12 PM),

https://www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/proof-of-stake-vs-

proof-of-work [https://perma.cc/FH27-GEUQ]; see also Proof-of-

authority vs. proof-of-stake: Key differences explained,

COINTELEGRAPH [hereinafter Proof-of-authority], https://cointelegraph.

com/blockchain-for-beginners/proof-of-authority-vs-proof-of-stake-key

-differences-explained [https://perma.cc/4BBP-ZU2B] (last visited

Mar. 24, 2023) (“The PoA consensus process grants a few . . . players

the authority to validate network transactions and update [the

542 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

business intermediaries, and customer-facing entities who

apply to operate nodes in the system and ensure all parties

are using a uniform data standard when relaying

information to the main chain.

68

Additionally, there would

be four sidechains: (1) a chain run by publishers, creators,

and collective rights organization nodes to log music

composition data (“Composition sidechain”); (2) a chain run

by record labels, recording artists, and distributor nodes to

log sound recording data (“Sound Recording sidechain”);

(3) a chain focused on tracking mechanical royalty

chain] . . . . The PoA consensus differs from the [Proof of Stake] in that

it uses identity rather than the digital assets . . . . Thus, a person’s

reputation is more valuable than their possessions . . . . Validators are

pre-approved by a group of “authorities” to verify transactions and

build new blocks. To be trusted, validators must adhere to a set of

requirements.”). PoA would also help create censorship-resistant

records. William M. Peaster, A Beginner’s Guide to ETH Validators,

BANKLESS (Sept. 20, 2022), https://newsletter.banklesshq.com/p/a-

beginners-guide-to-eth-validators [https://perma.cc/7CAK-Q2N9].

68

There are two types of blockchain transactions: on-chain

transactions and off-chain transactions. See Rohan Pinto, On-Chain

Versus Off-Chain: The Perpetual Blockchain Governance Debate,

FORBES (Sept. 6, 2019, 8:00 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbes

techcouncil/2019/09/06/on-chain-versus-off-chain-the-perpetual-blockc

hain-governance-debate/?sh=525fc1a61f5e [https://perma.cc/DUT3-

DZEA]; see also William M. Peaster, NFTs and the On-Chain

Spectrum, BANKLESS (Feb. 4, 2021), https://metaversal.banklesshq

.com/p/nfts-and-the-on-chain-spectrum [https://perma.cc/W3RH-FUR

J]. On-chain transactions are much more secure, but they take up more

space on the system, increase the power needed to add a new block to

the chain, and cost a lot more. See Jake Frankenfield, On Chain

Transactions (Cryptocurrency), INVESTOPEDIA (Aug. 24, 2021),

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/chain-transactions-cryptocurren

cy.asp [https://perma.cc/HTJ6-4ZW7]. Off-chain transactions are the

simpler, cheaper way to get something logged on the blockchain, but

they are much less secure. See Amanda J. Sharp, Note, Head in the

BitCloud: A Discussion on the Copyrightability and Ownership Rights

in Digital Art and Non-Fungible Tokens, 59 SAN DIEGO L. REV. 637,

651–52 (2022) (discussing the key differences between these

transaction types).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 543

Volume 63 – Number 3

accumulation (“MRR sidechain”); and (4) a chain focused

on tracking public performance royalty accumulation (“PRR

sidechain”). Sidechains are compatible independent

blockchains that supply information to the main chain, often

via rollups.

69

Blockchain rollups condense a sidechain’s

most important information into a data summary that gets

posted on the main chain for future reference and tracking

purposes.

70

The sidechain nodes inputting song ownership

data would be run by approved music-creation and business

intermediaries, while the sidechain nodes tasked with

collection of royalty distribution data would be run by

approved business intermediaries and customer-facing

nodes.

69

See Fuentes, supra note 56. Sidechains allow smart

contracts to be created within their chain and then deployed and tracked

on the main chain by using a universal base layer code. See Execution

Layer (EL) and Consensus Layer (CL) Node Clients (2022), ALCHEMY

(July 8, 2022), https://www.alchemy.com/overviews/execution-layer-

and-consensus-layer-node-clients [https://perma.cc/XUT8-7XFV].

70

See Fuentes, supra note 56; Stevens, supra note 56.

Figure 3

544 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

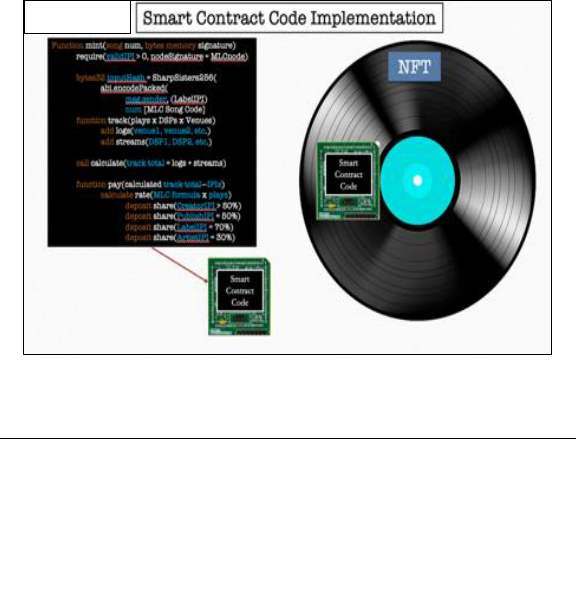

As Figure 3 shows, each sidechain would play a

crucial role in the data tracking and distribution process.

The Composition sidechain would ensure that creators and

publishers are accounted for and eradicate unclaimed works.

The Sound Recording sidechain would ensure that record

labels, recording artists, and distributors are compensated

and eliminate unmatched works. The MRR sidechain

would verify correct mechanical royalty data is processed,

while the PRR sidechain would track venue logs and

guarantee accurate public performance royalties are

distributed.

71

Blockchains eradicate data errors by employing

consensus mechanisms.

72

Consensus mechanisms require

at least fifty-one percent of a chain’s nodes to validate the

information before it can be recorded on the blockchain.

73

Within the MLC blockchain, the consensus threshold will

incentivize entities to log accurate data. Each of the four

71

The MLC blockchain would function on a Proof of Authority

consensus model that allows for the input of data, execution of data

validation mechanisms, and approval of validator nodes to run the side

and subchains. See Proof-of-authority, supra note 67 for a discussion

on blockchain consensus methods and Proof of Authority.

72

Employing an intermediary in the contracting process

increases the cost and slows down the processing time putting an

unfair, and unnecessary, burden on the artist. Smart Contracts and

Financial Services, DELTEC BANK (Feb. 15, 2022),

https://www.deltecbank.com/2022/02/15/smart-contracts-and-financial-

services/ [https://perma.cc/9J4R-5PWS]. Intermediaries are not

autonomous or decentralized, so they can easily take advantage of less

experienced or novice parties, but smart contracts do not need

intermediaries to verify their transactions and are reusable which

speeds up the process of logging information in the databases that

eventually determine what royalties each party is owed. See id.

73

This can work in the reverse via something referred to as a

51% attack. 51% Attack: Definition, Who Is At Risk, Example, and

Cost, INVESTOPEDIA, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/1/51-attack

.asp [https://perma.cc/9WUZ-X3E8] (last visited Apr. 24, 2023)

(“Owning 51% of the nodes on the network gives the controlling

parties the power to alter the blockchain.”).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 545

Volume 63 – Number 3

sidechains’ nodes would then take the information, confirm

it is correct by reaching a consensus across the chain, and

roll the data up so it can be logged on the main MLC

blockchain.

To ensure all parties remain invested in the

blockchain’s mission and incentivize accurate, timely

reporting, the MLC should require business intermediaries

and customer-facing entities to stake (i.e., provide for a set

time) a portion of their profits on the chain. Staking is like

placing money in a high-yield savings account—the staking

nodes contribute money to a fund that is used to help run

the blockchain and maintain its security.

74

While staking

has traditionally been done to incentivize investment and

participation in the block verification process, in the MLC

blockchain it would act as both an incentive and deterrent.

75

The staked profits would be returned to the entities on a

rolling basis. Nodes that consistently attempt to log

inaccurate data will be warned, suspended, or permanently

banned from partaking in future reporting.

Staking helps align the parties’ interests by ensuring

nodes are rewarded when the system performs successfully

and incentivizes all entities to work towards faster, fairer

royalty distributions. Additionally, the MLC could ensure

music-creation entities participate in good faith by making

future ownership dispute claims contingent on a showing

that reasonable effort was taken by the music-creation

individuals to input correct ownership data when first

registering the work. This would incentivize music-creation

74

Krisztian Sandor, Crypto Staking 101: What is Staking?,

COINDESK (Nov. 22, 2022, 9:43 AM), https://www.coindesk.com/

learn/crypto-staking-101-what-is-staking/ [https://perma.cc/67SH-JLG

P].

75

Ethereum 2.0 Staking: A Beginner’s Guide on How to Stake

ETH, COINTELEGRAPH, https://cointelegraph.com/ethereum-for-begin

ners/ethereum-2-0-staking-a-beginners-guide-on-how-to-stake-eth [http

s://perma.cc/8RGT-LJ4W] (last visited Mar. 24, 2023).

546 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

entities to contribute comprehensive composition and sound

recording data on the sidechains or risk losing the chance to

dispute inaccuracies later.

Once the initial blockchain is created and the nodes

are in place, the actual data collection and royalty

distribution should be self-executing.

76

No additional

administrative agency needs to be created to handle

disputes arising in connection with this technology as any

legal causes of action could be handled under the same

resolution avenues available to ordinary legal claims.

77

In

fact, not only could this solution revolutionize the way the

United States handles music royalty distribution, but

blockchain’s digital aspect could eventually allow for

global participation in data collection, which could one day

lead to the unification of the entire music copyright system.

The problems facing the music industry are international,

and by implementing blockchain, information can be

contributed from international entities, artists would have

better global protection against copyright infringement, and

fast, fair royalty payments could become a universal reality.

Employing blockchain technology verifies that

accurate information is logged in a universally accessible

database and creates uniformity by requiring all entities to

engage with identical, complete data sets. The

blockchain’s transparency allows all parties to access real-

time royalty information. The MMA laid the groundwork

for streamlined royalty regulation and distribution;

blockchain can take those ideas and make them tangible

solutions.

76

See infra Section IV.B.

77

For example, contract term interpretations, bad actors,

copyright infringement, etc.

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 547

Volume 63 – Number 3

B. Consistent, Automatic Royalty

Distribution—Smart Contracts

Historically, traditional contracts have solidified the

terms negotiated between parties, but they can create

discrepancies through nuanced interpretations and data

errors.

78

Traditional contracts also require parties to sign

separate documents and pay separate fees to complete a

transaction.

79

Smart contracts can tackle both inaccuracies

and inefficiencies. Smart contracts are neither smart nor

contracts; rather, they are computer codes that aid the

blockchain in recording transactions accurately by

automatically executing terms set in a multiparty

agreement.

80

“Smart contracts are tamper-resistant, self-

78

Paul Resnikoff, Welcome to the ‘Royalty Black Box,’ the

Music Industry’s $2.5 Billion Underground Economy, DIGITAL MUSIC

NEWS (Aug. 3, 2017), https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2017/08/

03/music-industry-royalty-black-box/ [https://perma.cc/K6CH-3Y9C].

Additionally, most administrative issues occur because humans

accidentally misreport or inaccurately input data. The music “royalty

black box” is a $2.5 billion economy where unclaimed, unmatched,

delayed, and other types of unpaid streaming royalties live. Id.; see

also Unmatched Royalties, FAIR TRADE MUSIC INT’L,

https://www.fairtrademusicinternational.org/campaigns/unmatched-roy

alties/ [https://perma.cc/TC4T-83NE] (last visited Mar. 25, 2023).

79

See John Ream et al., Upgrading Blockchains: Smart

Contract Use Cases in Industry, DELOITTE (June 8, 2016),

https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/signals-for-strategists/

using-blockchain-for-smart-contracts.html [https://perma.cc/MTN5-

FBFW].

80

Id. Blockchain revolutionized the application of smart

contracts by creating a shared database that runs on a decentralized

protocol allowing both parties to validate the transaction

instantaneously and facilitating the auto-execution of the smart contract

code without the input of a third-party intermediary. Id. The term

smart contract was first coined in 1996 by well-known cryptographer

Nick Szabo. Samuel Mbaki Wanjiku, Nick Szabo—Who Is He and

What Is His Influence on Modern Cryptocurrencies?, CRYPTO.NEWS

(Apr. 14, 2022), https://crypto.news/nick-szabo-who-is-he-and-what-is-

548 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

executing, and self-verifying.”

81

They decrease lag time

between transactions—as they execute functions

instantaneously upon command—and can carry out

unlimited functions in one single transaction making

separate fees and documents unnecessary.

82

The automated

nature of smart contracts makes them quick, and since they

require no intermediaries to execute transactions, they

ensure transparency between parties by assuming the

burden of transaction validator and executor.

83

his-influence-on-modern-cryptocurrencies/ [https://perma.cc/9FMZ-44

97].

81

Smart Contracts and Financial Services, supra note 72.

82

See id.

83

Id. (“[T]he smart contracts auto-execute [and] . . . validate

the outcome instantaneously and without need for a third-party

intermediary.”). The smart contracts used on the MLC blockchain

would be written in the BWARM Code—a code implementation created

by the MLC and its partners. Bulk Database Feed, THE MLC,

https://www.themlc.com/bulk-database-feed [https://perma.cc/8KWN-

FJTE] (last visited Mar. 25, 2023).

Figure 4

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 549

Volume 63 – Number 3

C. Music Mediums Revisited—CDs to MP3s

to NFTs

To really improve the music royalty system, smart

contracts and blockchain technology must work in tandem

to provide real-time, accurate royalty distribution. If

creators are the most valuable aspects of the music

industry, NFTs are their web3 equivalent.

84

NFTs are

unique and cannot be replicated.

85

While the word token

might suggest NFTs are associated with a physical coin,

NFTs are simply unique data strings that provide public

proof of asset ownership.

86

Similar to how a barcode on an

item of clothing marks the clothing’s price, tracks

inventory of that item, and can be referenced to verify that

an authentic purchase has occurred, NFTs can track digital

84

See generally Matthieu Nadini et al., Mapping the NFT

Revolution: Market Trends, Trade Networks and Visual Features, 11

SCI. REPS. 9 (2021); see also Aaron Mak, What Is Web3 and Why Are

All the Crypto People Suddenly Talking About It?, SLATE (Nov. 9,

2021, 5:45 AM), https://slate.com/technology/2021/11/web3-explained

-crypto-nfts-bored-apes.html [https://perma.cc/FEL4-36AG]; see also

Moxie Marlinspike, My First Impressions of Web3, MOXIE (Jan. 7,

2022), https://moxie.org/2022/01/07/web3-first-impressions.html [https

://perma.cc/S9U9-E2PB]; see also Luis Gallardo, Web3—Community,

Ownership, Decentralization, Utility, WORLD HAPPINESS FOUND. (Apr.

13, 2022), https://worldhappiness.foundation/blog/happiness/web3-

community-ownership-decentralization-utility/ [https://perma.cc/SH6B

-8G8B].

85

See Jacob Cass, What is an NFT? Starter Guide for

Designers, Artists & Creatives, JUST CREATIVE (Aug. 25, 2022),

https://justcreative.com/what-is-an-nft/ [https://perma.cc/GC62-XLC

M].

86

See Georgina Adam, But is it Legal? The Baffling World of

NFT Copyright and Ownership Issues, THE ART NEWSPAPER (Apr. 6,

2021), https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/04/06/but-is-it-legal-the

-baffling-world-of-nft-copyright-and-ownership-issues [https://perma.c

c/R5T5-RFRG] (“An NFT is just a link to a work of art stored on

another platform . . . .”).

550 IDEA The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for IP

63 IDEA 518 (2023)

asset ownership and verify a transaction’s authenticity.

87

NFTs are commonly used to track the sale of digital

artwork but can be used to track other copyrighted works.

88

NFTs are the vehicle that will accomplish the

MLC’s goal of uniform data tracking and streamlined

royalty distribution.

89

When a composition is created, the

music-creator entities would enter copyright information

into an MLC template that would generate a smart contract

programmed to execute that composition’s particular

royalty distribution functions.

90

That composition’s smart

contract would then be (1) recorded on the Composition

sidechain; (2) deployed each time a corresponding sound

recording is produced; and (3) included in a Composition

sidechain roll-up logged on the main blockchain. Then,

when a record label records a song using that underlying

composition, its sound recording metadata will be

automatically matched to the composition smart contract,

87

Cass, supra note 57.

88

See generally Sharp, supra note 68, for an in-depth

discussion on common NFT uses. ISWC codes, ISRC codes, IPI

numbers, Songwriter Split Sheets, etc. are all captured and recorded in

the NFT metadata. See supra notes 24, 25, 48, and infra note 92 for

detailed descriptions of each. The smart contracts within the NFTs

would track the length of time the song was played, the number of

engagements with that song from a particular streaming service during

a specific period, etc. The fair-use exception is outside the scope of

this paper, but the MLC and its committees would likely create some

sort of time limit that would qualify as de minimis use. For example, if

a song only played for 15 seconds or less, no royalties would accrue,

and no customer-facing entities would be charged.

89

See Chelsea Cohen, Note, Welcome to Web 3.0: A

Reevaluation of Music Licensing and Consumption to Level the

Payment Imbalance for Songwriters, 45 HASTINGS COMM. & ENT. L.J.

45, 73 (2023).

90

See David Idokogi, Note, Decentralizing Creativity: A

Tenable Case for Blockchain Adoption in the Entertainment Industry,

47 RUTGERS COMPUT. & TECH. L.J. 274, 293 (2021) (discussing how a

smart contract could calculate and streamline the distribution of fees

and royalties owed to all parties).

Smart Royalties: Tackling the Music Industry's Copyright

Data Discrepancies through Blockchain Technology,

Smart Contracts, and Non-Fungible Tokens 551

Volume 63 – Number 3

the sound recording royalty splits will be added to the smart

contract, and the completed song would be minted as an

NFT on the Sound Recording sidechain and added to the

main blockchain. The data logged on the sidechains would

be incorporated into the NFT tying the ownership and

descriptive metadata back to the creators themselves

through unique blockchain aspects like digital addresses and

wallets.

91

Incorporating digital addresses and wallets

directly into the song’s metadata would allow the artist and