COMMUNICATION SKILLS

FOR

ENGINEERS

SECOND EDITION

'U6XQLWD0LVKUD

8QLYHUVLW\RI+\GHUDEDG

'U&0XUDOLNULVKQD

2VPDQLD8QLYHUVLW\

&RS\ULJKW'RUOLQJ.LQGHUVOH\,QGLD3YW/WG

/LFHQVHHVRI3HDUVRQ(GXFDWLRQLQ6RXWK$VLD

1RSDUWRIWKLVH%RRNPD\EHXVHGRUUHSURGXFHGLQDQ\PDQQHUZKDWVRHYHUZLWKRXWWKH

SXEOLVKHU¶VSULRUZULWWHQFRQVHQW

7KLVH%RRNPD\RUPD\QRWLQFOXGHDOODVVHWVWKDWZHUHSDUWRIWKHSULQWYHUVLRQ7KHSXEOLVKHU

UHVHUYHVWKHULJKWWRUHPRYHDQ\PDWHULDOSUHVHQWLQWKLVH%RRNDWDQ\WLPH

,6%1

H,6%19789332501348

+HDG2IILFH$$6HFWRU.QRZOHGJH%RXOHYDUGWK)ORRU12,'$,QGLD

5HJLVWHUHG2IILFH/RFDO6KRSSLQJ&HQWUH3DQFKVKHHO3DUN1HZ'HOKL,QGLD

CONTENTS

Preface vii

INTRODUCTION INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND

COMMUNICATION 1

Information Technology In India and the Process of Communication 1

Communication: Aspects and Issues 2

Vitals of Communication 3

Creativity in Communication 5

Communicating with Concern and Empathy 6

The Johari Window 8

Interpersonal Communication 9

Body Language 11

Persuasive Communication and Negotiation 12

Roles We Take on During Negotiation 13

Summary 14

Review Questions 15

PART I GRAMMAR MATTERS 17

CHAPTER 1 TENSES, THE ACTIVE AND THE PASSIVE VOICE, AND

REPORTED SPEECH 19

Tenses 19

The Passive 31

Reported Speech 34

Summary 37

PART II COMMUNICATION MATTERS 39

CHAPTER 2 NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION: BODY LANGUAGE 41

The Communicating Body 41

Studying Body Language 42

Distance and Positioning 49

Body Orientation 50

Summary 54

Review Questions 54

iii

CHAPTER 3 LISTENING SKILLS 56

The Lynchpin of Communication 56

Hearing and Listening 56

Active Listening 57

Kinds of Listening 58

Barriers to Good Listening 61

Chinese Whisper 64

Good Listening 65

Summary 67

Review Questions 68

CHAPTER 4 SPEAKING AND NEGOTIATION SKILLS 69

The Art of Speaking 69

Speech Styles 70

Presentation Skills 73

Negotiation Skills 90

Summary 95

Review Questions 95

CHAPTER 5 READING SKILLS 96

Eye Movements and Chunking 96

Speed Reading 98

The SQ3R Method 102

Summary 104

Review Questions 104

CHAPTER 6 WRITING SKILLS 105

The Basics of Writing 105

The Process of Writing 107

Paragraph 109

Instructional Writing 112

Précis Writing 114

Abstract Writing 116

Note-Taking 119

Summary 121

Review Questions 122

CHAPTER 7 CREATIVITY AND MIND-MAPPING 123

Creativity 123

Times When We Are Creative 124

Contents

iv

Ways in Which You can be Creative 125

Developing Your Creativity 126

Factors that Block Creativity 128

Mind-Mapping: The Networking of Ideas 129

Mind-Mapping and the Learning Process 130

Mind-Mapping: Some Do’s and Don’t’s 134

Summary 136

Review Questions 136

CHAPTER 8 RÉSUMÉ WRITING, CURRICULUM VITAE (CV) AND

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE (SOP) 137

Deę nition of a Résumé 137

Guidelines for Eě ective Résumé Writing 140

Curriculum Vitae (CV) 143

Statement of Purpose (SOP) 148

Summary 152

Review Questions 153

CHAPTER 9 TEAM-TALK, GROUP DISCUSSION AND INTERVIEWS 154

Importance of Talk in a Team 154

ConĚ ict Management 156

Communication in Teams 157

Group Discussions (GD) 159

Structuring the GD 160

Interviews 162

Techniques of Interviewing 164

Preparing for an Interview 165

Kinds of Questions Expected at Interviews 168

The Interview Process 169

Summary 171

Review Questions 172

CHAPTER 10 TELEPHONE SKILLS, MEETINGS AND MINUTES 174

Telephonic Communication 174

Meetings 176

Minutes Writing 179

Summary 184

Review Questions 184

Contents

v

CHAPTER 11 BUSINESS LETTERS, TECHNICAL WRITING, E-MAIL WRITING 185

Business LeĴ ers 185

Business LeĴ er: Samples 190

Characteristics of a Good Business LeĴ er 193

Forms of Layout 197

Technical Writing 203

E-mail Writing 209

Summary 216

Review Questions 217

CHAPTER 12 REPORT WRITING, PROJECT AND PROPOSAL WRITING 218

Report Writing: Theory and Practice 218

Methods of Reporting 224

Proposal Writing 235

Summary 238

Review Questions 238

APPENDIX 239

Appendix A Vocabulary Expansion 241

Appendix B Common Errors in English Communication 254

Appendix C Practice Exercises 258

Appendix D Model Question Papers 264

Bibliography 275

Contents

vi

PREFACE

The learning and teaching of communications has generally been limited to the spoken and

the wriĴ en skills—presentations, group discussions, writing of leĴ ers, reports, etc. For stu-

dents enrolled in professional courses, it extends to document writing or maybe, project writ-

ing. Experience, however, shows that a good communicator has more than just these skill sets.

It is primarily an aĴ itude, a willingness to communicate, share one’s ideas and information

that makes one a good communicator. Language and the knowledge of the various formalities

associated with speaking and writing do maĴ er. However, given the right aĴ itudinal input,

communication becomes much easier and one emerges as an eě ective communicator.

This book discusses additionally these aĴ itudinal factors that make one a good commu-

nicator and links them up with the skill sets that enable eě ective communication. It speaks

of the writing and the speaking skills in the context of creativity, negotiation, interpersonal

skills and problem solving. Specię cally, the book aims at developing the communication skills

of Engineering and other professional students. For this target group, good communication

skills are necessary for recruitment and to enhance their opportunity for further growth in the

profession.

The book aĴ empts to locate the common communication needs of this group in diě erent

situations and to guide and equip the readers and learners to fulę ll them appropriately. The

book follows a skill-based approach. It isolates the skill sets required in diě erent communi-

cative situations, gives the students a comprehensive view of the requirements and ę nally

reinforces them further through exercises and activities.

Communication Skills for Engineers (CSE) thus is a comprehensive book that focuses on

the communication needs of users from the Engineering and other professional areas. It does

not look at “communications”—Ě uency in speaking and writing—in isolation but discusses

the whole aĴ itudinal framework that enables eě ective and purposeful exchange of informa-

tion. It aims at enabling students to identify and develop skill sets necessary to succeed in

their profession.

This second edition of CSE covers some additional topics that include a discussion of

grammar dynamics and activities thereof; information technology (IT) and communication;

the niĴ y-griĴ y of e-mail writing, interview skills; designing SOPs, a CV and Resumé writing,

and aspects of improving reading skills among others. This has been done to cater to a wider

range of felt needs among Engineering students and other professional students. To accom-

modate these additions, some of the earlier chapters have been collated appropriately. In this

process, we have tried our best to keep the book’s main points as well as its pedagogy intact.

We hope that the second edition of CSE will continue to help the students, teachers and

trainers from Engineering and other professional streams.

Acknowledgements

This book is a combined eě ort of many minds. It was conceived when we were teaching MBA,

and MCA students and took shape in the course of our lectures to B.Tech., B.E., B.A., B.Sc. and

B.Com. graduates. However, many inĚ uences have gone into its making. We would specially

like to thank the following people:

• Our teacher, Prof. N. Krishnaswamy, for his encouraging inĚ uence and useful advice.

He was instrumental in planting the idea of this book in our minds.

vii

• Late Prof. G. V. Raj for his valuable role in giving us the English language teaching

(ELT) orientation in our early days of teaching.

• Our students from Osmania University, Jawaharlal Nehru Technical University (JNTU)

and University of Hyderabad, whose responses and reactions helped to shape the con-

tents of the book in a big way.

• Prof. Tutun Mukherjee for her timely appreciation and for her assessment of our book

proposal.

• Dear friends like Vħ aya, Joy, Seetha and Srinivas for goading us to persevere in our ef-

forts and giving valuable suggestions and ideas.

• K. Srinivas, the then commissioning editor of Pearson Education who is now the pub-

lishing manager, for his relevant, practical and timely suggestions in the formative stag-

es of the book.

• Brig. Sambhi, former Principal of Karshak Engineering College, for his creative ideas

and suggestions.

• Our dear daughter, Shivani, for her growing understanding, and support and for hav-

ing put up with our preoccupied minds during the long months of writing.

Dr Sunita Mishra

Prof. C. Muralikrishna

Acknowledgements

viii

INTRODUCTION

Information Technology

and Communication

Objectives

This introductory section takes an overview of the role of Information Technology in communication

and also on the subject of communication. It discusses the different aspects and issues relating to com-

munication. It underpins the value of creativity in communication in addition to delving on interper-

sonal communication, body language, persuasive communication and negotiation.

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN INDIA AND

THE PROCESS OF COMMUNICATION

Many outstanding technologies have come into the lives of people towards the end of the 20

th

century. This is especially true in the ę eld of electronics. Many electronic types of equipment

like mainframe computers, mini computers, personal computers, e-mail, cell phones, i-pods,

and other gadgets have become part of our lives. In this informaton age, we come across a lot

of personal or oĜ ce data that needs to be processsed by computers and this is called informa-

tion technology or IT.

Information technology (IT) accounts for a signię cant part of India’s GDP and export earn-

ings, while providing employment to a large number of its tertiary sector workforce. Techni-

cally equipped immigrants from India have been seeking jobs in the western world since the

1950s as India’s education system produced more engineers than its industry could absorb.

Thus, India’s growing stature in the information age enabled it to form close relations with

both the United States of America and the European Union.

Out of around 400,000 engineers produced per year in the country, approximately, about

100,000 are well equipped in both technical competency and the English language skills. India

has developed a number of outsourcing companies specializing in customer support through

the Internet or telephone. For instance, by 2008, India had a total of 49,750,000 telephone lines

in use, a total of 233,620,000 mobile phone connections, a total of 60,000,000 Internet users—

comprising 6.0% of the country’s population, and 4,010,000 people in the country had access

to broadband Internet— making it the 18th largest country in the world in terms of broadband

Internet users. Total ę xed-line and wireless subscribers reached 325.78 million in June, 2008.

Communication Skills for Engineers

2

On the other hand, from the dynamics point of view, it needs to be mentioned that Manage-

ment Information Systems (MIS) has assumed vital importance. MIS is the application of IT to

the communication process in organizations. Generally, in MIS most of the information pro-

cessing is done by the computers. The span of activities undertaken by MIS includes among

others generating, processing and transmiĴ ing information. MIS is used for interpersonal and

organizational communication in addition to strategy planning and improving customer care.

Thus, managers can seek vital clarię cations, information from and give instructions and direc-

tions to fellow-personnel of the organization through the systems.

An important eě ect of IT on organizations is one of leveling. Personnel in organizations,

whether they are superiors or subordinates, work in an information-sharing ambience where

everybody is involved non-hierarchically in the developmental work of the organization. In-

terestingly, the IT age continues to demand proę ciency in English communication skills from

most of its initiators, mid-level force and end-users. It is in this context that one needs to look

at the niĴ y-griĴ y of communication.

COMMUNICATION: ASPECTS AND ISSUES

When American playwright and diplomat Clare Boothe Luce visited George

Bernard Shaw in his London Ě at years ago, she found him writing at his desk.

To express her admiration, she began, “Mr Shaw, you are the only reason I’m

standing here.”

Shaw looked up and replied, “Who did you say your mother was, my child?”

(Reader’s Digest)

Communication, as we see it here, can be a complicated process of give-and-take with

innumerable intricacies and dimensions. OĞ en, however, it is seen as a set of competencies,

primarily including the wriĴ en and the spoken mode. It is taught as a package involving

training in skills pertaining to writing, speaking, reading and listening (L. S. R. W). But gen-

eral observation shows that eě ective communication involves a lot more than proę ciency in

the L. S. R. W skills. More than language, it needs an aĴ itude, a willingness to give and take; to

open up to others and accept others; to have empathy and capacity to look at situations from

varied perspectives. Given these aĴ itudinal factors, language becomes just an aid to promote

communication. This chapter aims to give an overall view of most of these important factors

and show how they enable communication.

A complicated process in itself, communication takes place all around us all the time. In

fact, we all spend around 70% of our time receiving or sending messages. Essentially, it in-

volves the sender or the communicator, and the receiver. It is sent in a certain medium through

encoded messages. The receiver, in turn, decodes the message and sends back the reactions

to the sender in the form of feedback. The beauty of the whole process, however, lies in the

nature of communication itself. Language, be it in any form, has the potential to mean many

things at the same time. Thus, the sender sends a message, which the receiver is free to make

meaning of depending on the mode of transmission, the kind of encoding and of course, more

importantly, the receiver’s own state of mind while receiving the message.

Introduction

3

VITALS OF COMMUNICATION

The features that have been looked into in this section are, function of language and elements

of human communication.

The Function of Language

Language embodies and conveys thought. It is an important means that we rely on to convey

our thoughts and feelings. In its spoken and wriĴ en forms, language is the commonest and

most important means of communication in all social activities among human beings. Along

with language there are other elements, which contribute to communication. In the following

section, some of these elements are brieĚ y examined.

Elements of Human Communication

Human communication, as a process, is not a dull and passive process. It is a dynamic and

active process comprising several important elements. These elements may be enumerated

as follows:

1. Initiation: Communication begins when a source initiates a statement. A statement is ini-

tiated in order to transmit some thought, need, idea or information. The receiver aĴ ends

to the statement transmiĴ ed by the source, interprets the statement and decides how to

respond.

2. Feedback: The response of the receiver that is sent back to the source forms the feedback.

The source modię es further statements based on the feedback. Feedback helps the source

to know if the message was received correctly or not.

3. Channel: Channel connects the source (e.g. a speaker) and the receiver (e.g. listener). A

speaker and a listener are connected to each other by sound waves and (or) the light

waves. That is, language carried by sound waves; and facial expressions and body ges-

tures carried by light waves.

4. Situation: Situation is the place or seĴ ing in which a communicative event occurs.

5. Purpose: Purpose consists of the intention of the source, or speaker. It is the communica-

tive aim of the speaker.

6. AĴ itudes: The speaker and the listener, carry with them certain ideologies, world-views,

beliefs, likes, dislikes and aptitudes. They are also under the inĚ uence of varying emo-

tional and mental states. These factors aě ect the aĴ itudes of the speaker and the listener

at the time of communication.

7. Knowledge: The speaker has to possess adequate knowledge of the message that is to be

transmiĴ ed. Knowledge that is based on observation, study and personal experience

helps the speaker to communicate eě ectively.

8. Expression: Expression consists of the ability to transmit or communicate. Fluency, clar-

ity and intelligibility of expression pave the way to eě ective communication. The Ě ow of

information, as embodied in the message that is transmiĴ ed, is smooth when expression

Communication Skills for Engineers

4

is clear. This helps the speaker and the listener to avoid communication gaps and also

arrive at consensus and decisions. Improper or faulty expression leads to breakdown of

communication.

9. Language: Language is one of the most important elements of the communication process.

The eě ective use of language consists in selecting appropriate words and paĴ erns of sen-

tences while communicating. These linguistic paĴ erns, suitably supported by facial and

body gestures, enable eě ective communication.

10. Intellectualism: Communication is sustained and it becomes eě ective only in an intellec-

tual ambience. That is, the speaker and the listener have to express and understand views

calmly, rationally, reĚ ectively, precisely and eĜ ciently. When intellectualism is absent,

thoughts and ideas are likely to be ineě ectual.

See What This Communicates!

Once upon a time, there were four people. Their names were Everybody, Some-

body, Nobody and Anybody. Whenever there was an important job to be done,

Everybody was sure that Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it,

but Nobody did it. Everybody got angry because it was Everybody’s job. Ev-

erybody thought that Somebody would do it, but Nobody realized that nobody

would do it. So consequently, Everybody blamed Somebody when nobody did

what Anybody could have done in the ę rst place.

ACTIVITIES

1. Read the sentences below (A) and see in how many diě erent contexts you can use

them. Create small contexts around them and use them to illustrate the given modes

of expression(B). Add more to the list if you can.

A B

a. The door is open. Giving information

Making an oě er

Rejection

Acceptance

b. You are joking! This can’t be true. Extreme happiness

Shock

Anger

c. The possibilities are endless. Appreciation /Frustration

Amazement /Confusion

Introduction

5

2. Try to read the following groups of sentences separately stressing the underlined word.

Make a note of the diě erent meanings that emerge.

(A)

Even he does not write regularly.

Even he does not write regularly.

Even he does not write regularly.

(B)

You don’t know me?

You don’t know me?

You don’t know me?

(C)

Yes. I don’t remember.

Yes. I don’t remember

Yes. I don’t remember

(D)

Is this possible?

Is this possible?

(E)

I can’t write the examination.

I can’t write the examination

I can’t write the examination

CREATIVITY IN COMMUNICATION

While doing the above exercises, you must have realized that responding to a communica-

tional situation needs creativity. The meaning has to be always put together like the pieces of a

jigsaw puzzle. One always has to “make” the ę nal picture for oneself. When we talk of creativ-

ity in communication, we mean the capacity to read hidden messages, to see a link not seen

before, to infer the unsaid, unspelt consequences or even to tailor a response that can alter a

communication situation to one’s advantage! A wiĴ y creative receiver can create meanings in

the encoded message the sender had never imagined. Creativity in day-to-day interactions is

also one’s ability to break out of stereotyped reactions, to see beyond the set, accepted paĴ erns

and give a novel twist to existing “reality” or beĴ er still, create a “reality”!

Albert Einstein was travelling to universities in a chauě eur driven car, deliver-

ing lectures on his theory of relativity. One day while in transit, the chauě eur

remarked:

“Dr.Einstein, I have heard you deliver that lecture thirty times. I know it by

heart and bet I could give it myself”. “Well, I will give you the chance,” said

Einstein. “They don’t know me at the next college, so when we get there I’ll put

Communication Skills for Engineers

6

on your cap, and you introduce yourself as me and give the lecture”. The chauf-

feur delivered Einstein’s lecture Ě awlessly. When he ę nished, he started to leave,

but one of the professors stopped him and asked a complex question ę lled with

mathematical equations and formulas. The chauě eur thought fast. “The solu-

tion to that problem is so simple”, he said, “I’m surprised you have to ask me. In

fact, to show you just how simple it is, I’m going to ask my chauě eur to come up

here and answer your question.”

— Readers Digest

ACTIVITIES

3. Given below, is a list of ten sentences. Take one minute to think about each and talk on

it for a couple of minutes.

The sky is blue

The height of success.

The ceiling is very high.

Bicycling under water is fun.

Classes are not to be aĴ ended.

It is fun to fail.

Among the stars.

Children are mean.

The blackboard is green.

My useless fridge.

4. Try to establish links between the pairs of objects given and talk about each of the

pairs.

Apple // Computer

Horse // House

Armchair // Fridge

Star // College

Pigs // Saints

Trees // Chocolates

Hill // Eagle

Insect // Money

Bird // Ceiling

Chair // Piano.

COMMUNICATING WITH CONCERN AND EMPATHY

Very oĞ en we come across managers who would say: “I do a lot for my employees. I expect a

lot out of them. I work hard to be friendly towards them and treat them right. However, I feel

Introduction

7

they are ungrateful. I think if I stayed back at home for a single day they would waste time at

the oĜ ce canteen. What can I do to make them independent and responsible?”

Problems like this are common. A large part of it is because we fail to communicate our

concern or empathy. A very closely related quality that plays an equally important role in com-

munication is empathy. Empathy is a quality that will allow you to understand the mental

and psychological state of the person we are communicating with. This will help us to adapt

our response and pitch it at an acceptable and appropriate level. Important here is the con-

cept of empathetic listening, which can be explained as listening with a view to understand.

We generally listen with an intent to reply. Most of the times, we are either talking or geĴ ing

ready to talk. When we listen, we generally listen at one of the four levels. We may be ignor-

ing the person, not really listening at all. We may be pretending to listen. We may be doing

selective listening, hearing only certain parts of the conversation, or we may be practising at-

tentive listening, paying aĴ ention to every word that is being uĴ ered with utmost care. What

is required oĞ en, however, is empathetic listening that forms the ę Ğ h grade of listening.

This is something beyond the skill-based acquisition of the skill. Here listening is done with

a purpose to understand, to see the world from the speaker’s perspective intellectually and

emotionally, but not necessarily agree with the speaker. This kind of listening has an almost

therapeutic eě ect on both the speaker and the listener, primarily because it gives a person a

“psychological air”. This “psychological air” deeply impacts communication, expanding both

the speaker’s and the listener’s area of inĚ uence on one another. Paradoxically, this kind of

listening is also risky. To listen deeply, one also has to open oneself up and become vulnerable.

To have inĚ uence, thus, one has to risk being inĚ uenced.

The poet doesn’t invent. He listens.

—Jean Cocteau

Listening to a Disturbed Person

At some point or the other, all of us have been disturbed or we have interacted

with people who are disturbed. It could be a friend who feels that injustice has

been done to him/her at the workplace, or a neighbour whose feelings have been

wounded.

Some people are good at expressing their hurt feelings, some are not. Some-

times, we even try to suppress them and push them to the back of our mind. But

unexpressed feelings do not disappear. They are like springs. You push them

down but they express themselves sooner or later, may be at the wrong place or

time.

A person who has suppressed feelings cannot act or think straight because

he/she does not feel straight. Only aĞ er the feelings are released can the per-

son think straight and look into the problem objectively. Above everything else,

more than advice, evaluation or judgement, a disturbed friend needs to fulę ll

the desire to be understood.

Do not listen to their words, listen to their feelings. Respond with the whole of

yourself. The best way to ‘talk’ to a disturbed person is to listen.

Communication Skills for Engineers

8

THE JOHARI WINDOW

The concept of the Johari window is an important idea that explains factors behind mutu-

al understanding. Named aĞ er Joseph LuĞ and Harry Ingram, it explains communications

along two dimensions: exposure and feedback. Exposure is the extent to which the individual

is willing to divulge his feelings and information in trying to communicate. Feedback is the

extent to which the individual manages to elicit exposure from others. They translate these

factors into four windows—open, blind, hidden and unknown (see Fig.1). The “open” win-

dow is the information about you, which you as well as others can see. The “blind” window

encompasses the factors about you that others can see but not you.

This, oĞ en, is the result of your defensive behaviour that prevents

others from telling you things about yourself. The “hidden” win-

dow is the information known to you but unknown to others. These

include facts about yourself that you hide from others. Finally, the

“unknown” constitutes factors that that neither you nor others are

aware of. Advocates of the Johari window see openness, authentic-

ity and honesty as valued qualities in interpersonal relationship.

They also imply that it is in the interest of the individual to expand

the size of the “open” window, increase self-disclosure and be more

willing to listen to feedback from others about oneself.

ACTIVITIES

5. Select a relationship in your life where your emotional account is nil. Write ę ve reasons

from your perspective on why you think the situation is so. Now try and approach the

problem from the other person’s point of view and review the situation. Were your as-

sumptions all correct?

6. Give ę ve reasons for and against the statements given below.

1. Siblings can be your best Siblings are one’s greatest

friends because, enemies because,

a.

a.

b. b.

c. c.

d. d.

e e.

2. You are your greatest friend You are your greatest enemy

because, because,

a. a.

b. b.

c. c.

d. d.

e. e.

Open Blind

Hidden Unknown

Figure 1: Johari Window

Introduction

9

3. Holidays are wonderful Holidays are not wonderful

a. a.

b. b.

c. c.

d. d.

e. e.

4. Higher education should be Higher education should not be

subsidized subsidized

a. a.

b. b.

c. c.

d. d.

e. e.

5. Children are cruel Children are not cruel

a. a.

b. b.

c. c.

d. d.

e e.

7. Recall any incident in your life, which brought forth in you something that, belonged

to the “unknown window” till then. How have you been managing that aspect/quality

since then?

8. Imagine, you have just died and your friends want to put up your picture in your class

with the following words wriĴ en below:

“Here was a person who… ”

Complete the paragraph in about 30 words.

INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

I can live two months on a good compliment.

—Mark Twain

Possessing good knowledge of interpersonal relations and being able to achieve the delicate

balance that communication requires goes a long way in ę ne-tuning our reĚ exes to achieve

eě ective communication. For instance, it would be extremely inappropriate on our part to

complain to a new recruit at our oĜ ce against the boss or a nagging spouse at home. It is very

important to be able to decide who should be told what, when and how.

Communication is generally divided into ę ve levels, depending on the nature, scope and

depth of interaction:

Communication Skills for Engineers

10

Passing Communication

This refers to the daily niceties or phatic communication paĴ erns like “hello, good morning”

and “good night” etc. The purpose here is to merely acknowledge the person’s presence. Here

a detailed response is neither expected nor given. When somebody wishes you in oĜ ce say-

ing “Hello! How are you?” you deę nitely do not sit back and say, “Not well at all! Know what

happened on the road today?…”

Factual Communication

OĞ en, most of the organizational work depends on the exchange of factual information. Giv-

ing instructions, evaluating and passing on information accurately and concisely fall under

this category. Interpersonal communication is carried on here with minimal possible emo-

tional risk. Examples of such communication are: Is the report ready? Has the new employee

joined today? How many more customers are there to meet?

Thoughts and Ideas

Here, the exchange is at a slightly higher level of communication. This includes exchange of

ideas that suggests a more involved interpersonal communication. However, it also throws

open the possibility of rejections – hence, the risk involved is more.

Feelings

The feeling level of communication involves a higher degree of risk. During this kind of in-

teraction, there is exchange of sentiments and feelings making the sender vulnerable to rejec-

tion.

Peak Communication

This is the highest level of communication that is most diĜ cult to achieve. It ensures perfect

understanding between two individuals or a group of individuals. Creativity and a synchro-

nized work culture are the building blocks of this kind of communication.

A bore is a man who, when

you ask him how he is, tells you.

—Bert Leston

ACTIVITIES

9. Look at the statements given below and categorize them into the diě erent communica-

tion levels.

1. Oh God! It’s late already.

Introduction

11

2. Will you ever learn to see straight?

3. I think we have reached the end of the road.

4. How do you do?

5. It’s rather late, isn’t it?

6. I agree that capitalism has its merits but we can’t overlook its demerits.

7. We all agree. We can achieve this together.

8. Have you received any answer to the leĴ er?

9. It is a pleasure working together. How else do you think we have survived our

boss?

`10. I strongly believe that the developed countries are causing more harm to humanity

than the underdeveloped ones.

10. Complete the following incomplete dialogue using three diě erent situations illustrat-

ing the 2

nd

and 3

rd

levels of communication:

A.

B. Oh yes! I know.

A.

B.

A . Sure. I’ll remember.

People who feel good about themselves produce good results.

—Henneth Blanchard and Spencer Johnson.

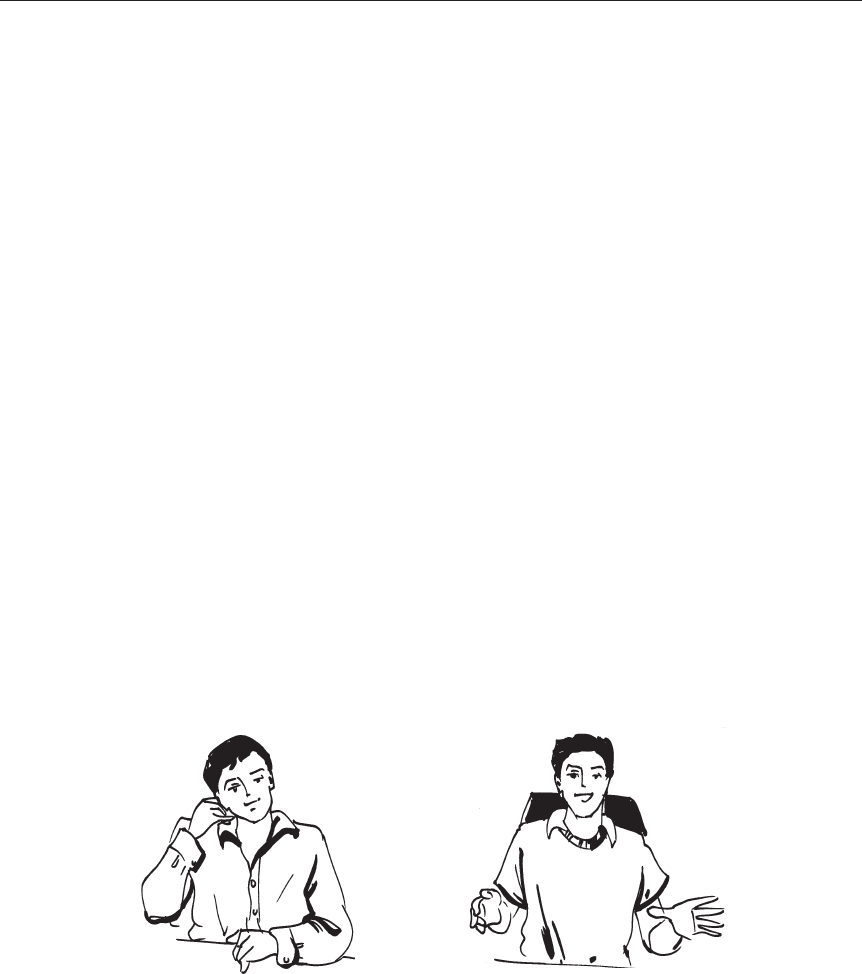

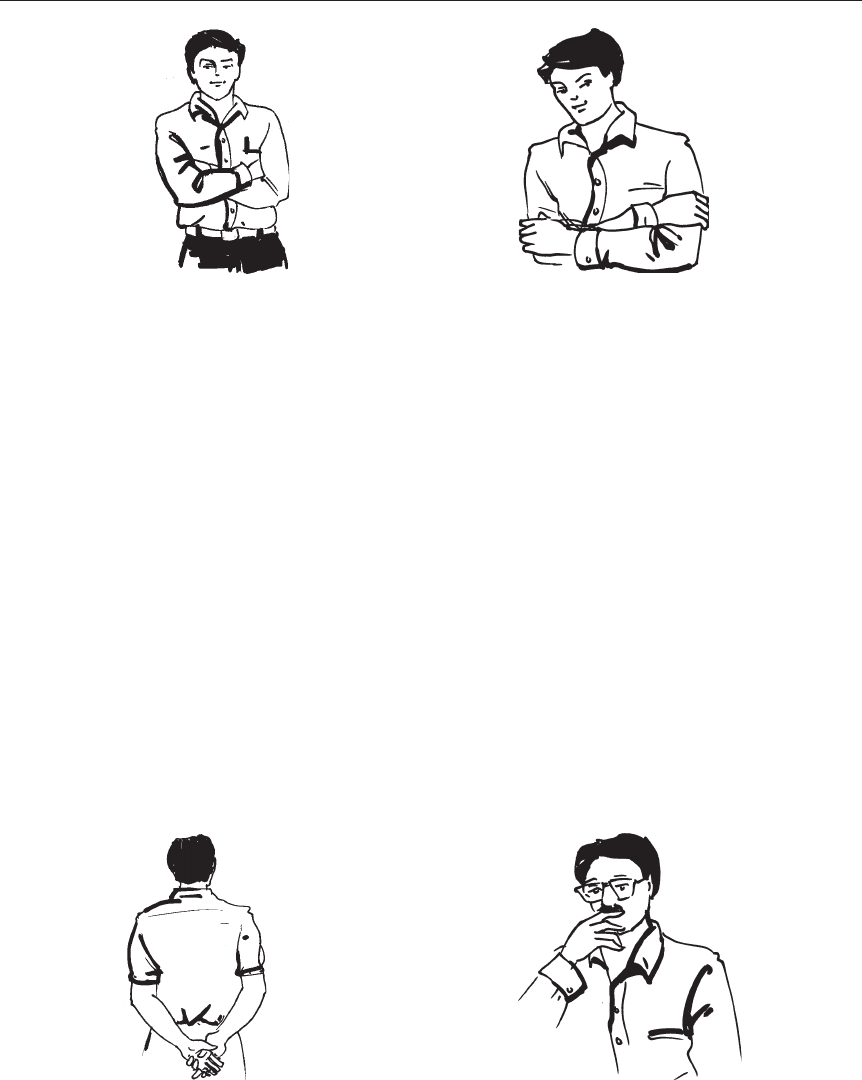

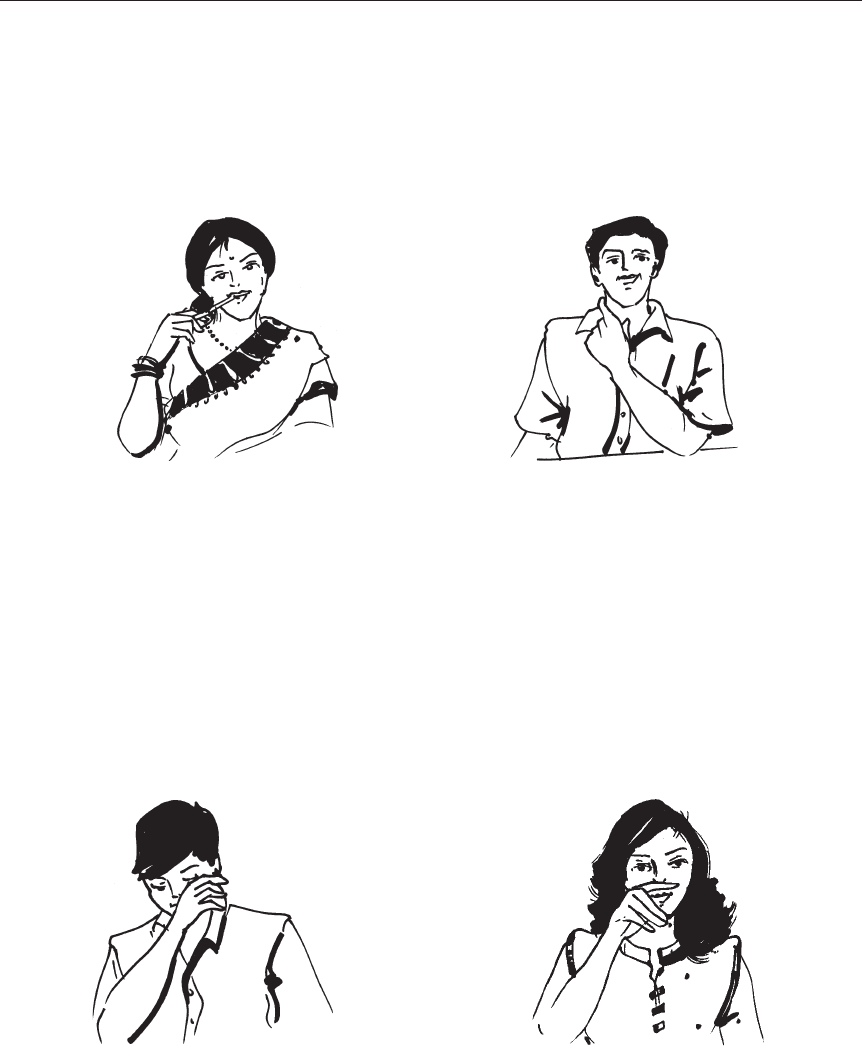

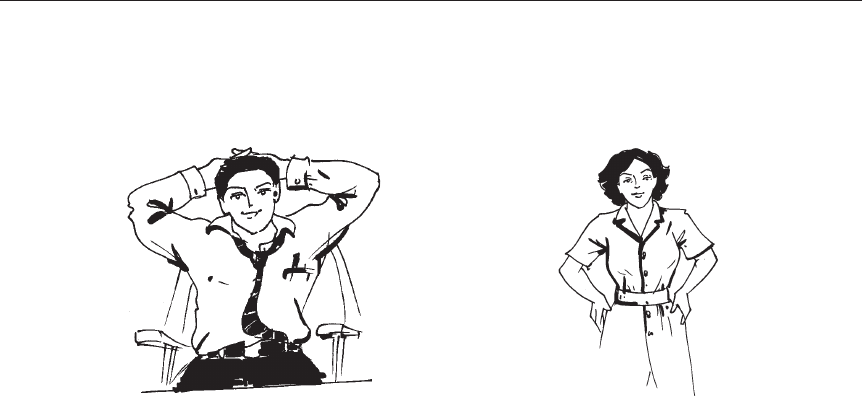

BODY LANGUAGE

Body language is an important factor that one has to keep in mind while communicating.

Most of our communication in every day maĴ ers takes place through body language. Most

important are the gestures, the tone and the facial expression. If the spoken words do not

match the body language, it is the message covered by the body language that creates the ę nal

and lasting impression.

The body language of the person who is being spoken to is of immense importance for a

good communicator. It is an important feedback not only to decide how one’s message has

been accepted but also to determine whether it is the right time to convey the message at all!

Arms folded around one’s chest, for example, can signify a defensive aĴ itude. It could

mean “I don’t want to know” or “I feel vulnerable as you talk to me”. If the ę sts are clenched,

in addition, it suggests holding back of emotion or information; ę nger on the lips while speak-

ing can show incongruence of thought or speech. Looking away while someone is speaking or

rubbing the eye deę nitely suggests avoidance. The siĴ ing posture also can signify the aĴ itude

Communication Skills for Engineers

12

of the speaker. Reversing the chair and siĴ ing, or leaning over the back can indicate power

and control. Slumping with arms folded or clasped on the lap can convey dejection or submis-

siveness, while leaning back on the chair with legs crossed and hands behind the back signify

authority, the “I don’t need to fear you at all!” aĴ itude.

While it is necessary to consider body language as an important clue in the communicative

process, one should also remember that it is largely situational. They do not mean anything by

themselves, but acquire their precise meaning only in association with other symbols.

ACTIVITY

11. Given below is a list of ten activities. Form groups of two and enact the situations with-

out talking. Ask the class to guess the situation. Discuss the responses and clues on the

basis of which they formed their opinion.

a. A father is indignant because he feels his son is going astray and not concentrating

on his studies. The son feels his father is unnecessarily pressurizing him.

b. Two friends have met aĞ er a long time at a party. They are overjoyed to ę nd one

another and are engrossed in their talk.

c. You are trying your best to convince your client that the soĞ ware you have newly

developed will work. He, however, is sceptical about the whole product.

d. Your teacher is trying hard to explain a concept to you. In between, he forgets a

name and is trying hard to recollect it.

e. Your subordinate is trying hard to Ě aĴ er and praise you. You, however, are very

suspicious of his motive .You want to tell him so, but you are holding back out of

courtesy.

f. Your friend has come to you with a grave professional problem. You are thinking

hard of the possible solutions. Your friend, too, is troubled.

g. You are a junior employee in a company. The company is facing a ę nancial crisis and

laying oě people. You have been called into the boss’s room and asked to sit. The

boss looks grave and you are nervous.

h. A colleague is very enthusiastically trying to explain a plan to you. You are alert,

eager and taking in every word.

i. You are wild with your employee but trying to control your anger. Your employee is

conscious of his guilt and is apprehensive.

j. You are worried, tensed and very confused. Your friend is trying to cool you down

and comfort you. She is strong, cool and conę dent, but very concerned.

PERSUASIVE COMMUNICATION AND NEGOTIATION

In the ę lm titled “The Shop Around the Corner”, a character says, “when my

boss calls me an idiot, I agree. AĞ er all, I’m no fool.”

—Readers Digest.

Introduction

13

OĞ en we judge situations, decide our role in the context and react in the way we consider

appropriate. A very important skill that is used subtly in all communication situations is “ne-

gotiation”. To be able to negotiate during communications, one has to be ę rst conscious of

one’s role and also see how others perceive it. This is followed by each participant demarcat-

ing his area of operation and negotiating space, and deciding whether and how much to em-

power the other participant. The next stage is one where the exchange is decided. The terms

and conditions here are largely a fallout of the ę rst two factors.

The nature of exchange one proposes or accepts depends on the role one has ę xed for

oneself and also the degree of empowerment that has been negotiated and agreed upon. The

next and ę nal stage can be called the disclosure stage that comes by if the ę rst three stages

have been positively set. At this stage, participants let down their barriers and are willing to

disclose information about themselves. This stage is risky, but it also paves way for successful

“peak” communication. Participants moving through exchange and disclosure stage commu-

nicate with a high sense of interpersonal rapport.

ROLES WE TAKE ON DURING NEGOTIATION

Psychologists believe that the roles we take up during interaction are either that of the parent,

the adult or the child. The parent role largely constitutes the “that is how it is” aĴ itude. It also

includes admonitions, giving rules, laws and value judgments. The child is the impulsive and

emotional aspect of a person that can throw tantrums and get depressed. Simultaneously, it

also includes creativity and curiosity of a person. The third side to an individual is his adult

– the aspect that weighs, decides and displays appropriate emotions and expressions. During

interpersonal communication, transaction can take place between similar roles in individuals

or between diě erent roles. The negotiation could be between the parents in two individuals,

between the parent in one and child in another or between the adult in one and parent in the

other. What is important here is that, during negotiations one should be conscious of the role

he himself is playing, recognize the role the other is adopting and react accordingly. Some of

the factors that play an important role while negotiating successfully are given below:

• Be conscious of the way you and your participants have positioned yourselves and the

factors that each is looking for in the communication situation.

• It helps oĞ en if the participants are fair and willing to commit themselves. A commu-

nication situation built on a sense of fairness and trust can result in strong, satisfying,

lasting relationships.

• We oĞ en conclude that our win depends on somebody’s loss and we work towards a

win-loose situation. Eě ective communication situations however are oĞ en built around

win-win situations. The situation allows both parties to beneę t or empower themselves,

either materially or emotionally.

Two Most Common Traits of Managers Who Failed

1. Rigidity: they were unable to adapt their style to changes. They were unable to re-

spond to feedback. They couldn’t listen or learn.

2. Poor relationships: they were harshly critical, insensitive or demanding. They alien-

ated those when they worked with.

Communication Skills for Engineers

14

ACTIVITY

12. Given below are two situations. Analyze them, discuss what kind of negotiation situa-

tion they project and think of solutions.

a. An old piano is for sale. The prospective buyer and the seller agree on the cost. The

buyer ę rst wants the chair and then the musical pages to be given free. The seller

agrees. Encouraged, the buyer next wants the delivery also to be done free.

b. Ravi is the head of a designing team in a company producing electrical equipments.

He has a good team, he gives innovative ideas and leads them from the center. Of

late, however, he has been experiencing burn out, and exhaustion. He has spoken to

the boss and arranged for a two-week vacation with his family. A week before leav-

ing, the company gets the news that top executives from an internationally reputed

company will be coming for a visit to see the prototypes developed. Ravi’s boss

feels that he should stay back and take care of the presentation since he himself has

designed most of the products and is the backbone of the team. He even thinks that

with his impressive persuasion he might be able to increase the budgetary alloca-

tions for the department. Ravi, however, feels that he must go because the team can

take care of the presentation. His wife too has arranged for leave in her oĜ ce and it

will not be possible to postpone it for a later time.

SUMMARY

• The IT age reinforces the continuing demand for proę ciency in English communication

skills from most of its initiators, mid-level force and end-users.

• Communication is a complicated process of give-and-take with innumerable intricacies

and dimensions.

• For communication, more than language, what is needed is an aĴ itude, a willingness to

give and take; to open up to others and accept others; to have empathy and a capacity

to look at situations from varied perspectives.

• Creativity in day-to-day communication is one’s ability to break out of stereotyped re-

actions, to see beyond the set and accepted paĴ erns.

• Empathy is a quality that will allow one to understand the mental and psychological

state of the person we are communicating with.

• The two dimensions of communication, according to the Johari window are, exposure

and feedback. These can be looked at through four windows—open, blind, hidden and

unknown.

• It is always desirable to expand the size of the ‘open window’, increase self-disclosure

and be more willing to listen to feedback from others about oneself.

• Passing communication, factual communication, thoughts and ideas, feelings and peak

communication are the ę ve levels of communications based on the nature, scope and

depth of interaction.

Introduction

15

• Much of eě ective communication is non-verbal. Body language is an important factor

of the non-verbal communication.

• Negotiation depends on the nature of exchange one proposes or accepts. It depends on

the role one has ę xed for oneself and the degree of empowerment that has been negoti-

ated and agreed upon.

• The roles people take during interaction can be that of the parent, the adult or the

child.

• Eě ective interpersonal communication depends on appropriate handling of these three

roles.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. What is Information Technology?

2. What are the eě ects of MIS on organizations?

3. What is communication?

4. What factors are necessary for eě ective communication?

5. What is creativity in the context of day-to-day communication?

6. What is the function of language?

7. What are the elements of human communication?

8. What is empathy?

9. What do you understand by the term ‘Johari window’?

10. What are the implications of the Johari window?

11. What are the diě erent levels of communication?

12. How are these levels of communication related to interaction?

13. How is the nature of a specię c interaction determined?

7KLVSDJHLVLQWHQWLRQDOO\OHIWEODQN

PART 1

Grammar Matters

7KLVSDJHLVLQWHQWLRQDOO\OHIWEODQN

CHAPTER 1

Tenses, the Active and the Passive

Voice, and Reported Speech

Like everything metaphysical,

the harmony between thought and reality

is to be found in

the grammar of the language.

—Ludwig WiĴ genstein

Chapter Objectives

This section aims to give the students the basics of grammar. It deals with tenses, the active and the

passive voice and the reported speech. It also deals with the main and auxiliary verbs, the fi nite and the

non-fi nite verbs and the way they are used in the different tense forms. The chapter deals with grammar

within very limited space. Hence, only some of the very important concepts have been dealt with.

TENSES

The verb The verb is one of the most important elements of English grammar. It can be de-

scribed as a word that expresses action in a sentence. Look at the following expressions.

a. You wait patiently.

b. You wait.

c. Wait patiently.

d. Wait.

e. patiently

f. you

Communication Skills for Engineers

20

The fi rst four here can be seen as complete expressions. They can stand alone. The last two, however,

cannot be independent. The main difference between them, if you see closely, is that the last two do not

have a verb. It is the verb that forms the nucleus of a sentence. Hence, it makes the sentence meaningful.

We can have a sentence with only the verb but there cannot be any sentence without a verb.

The Main and the Auxiliary Verbs

Now, look at the following sentences:

a. Children play happily.

b. We can do the work in three days.

c. The workers have been working overtime.

d. The typed papers had been lying on the table for months when the enquiry was made.

In the ę rst sentence, the verb is “play”. It expresses the action in the sentence. But in the

second sentence, the verbs are, “can” and “do”. And in the third sentence, “have”, “been” and

“working’ are verbs. These verbs, however, are not similar. They are either the main or the

auxiliary verb. Generally, words like “play”, “do” or “work” are the main verbs. And words

like “can”, “have”, “been”, etc, are the auxiliary verbs. It could be said that words that express

the action in a sentence are the main verbs while verbs that help determine the time frame are

auxiliary verbs. The following are the categories of words we use as auxiliaries.

“Modal” forms -- can, could; will, would; shall, should; may, might; must, ought to.

“Be” forms – is, am, was were, are.

“Have” forms—have, has, had.

Now, change the tense of the sentences given above:

a. Children played happily.

b. We could do the work in three days.

c. The workers had been working overtime.

d. The typed papers have been lying on the table.

We ę nd in each of the cases that one of the words identię ed as the auxiliary verb changes

the form in case of a tense change. But in case there is no auxiliary verb, the main verb changes

its form (as in the case of the ę rst sentence).

A sentence will always have only one main verb. But it can have one or more than one

auxiliary verbs.

Look at some more sentences:

a. Man is mortal.

b. This city has an eĜ cient government.

c. All children are creative by nature.

d. Dinosaurs were both vegetarian and non-vegetarian.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

21

These sentences have the words we have earlier identię ed as auxiliary verbs. But as you

see, they are the only verbs in the sentence. Hence, they are the main verbs in these sentences.

One proof of this is that, in case of a change of tense too, these forms will undergo change.

ACTIVITY

1. Look at the following sentences and identify the main and the auxiliary verbs in each.

Point out when the main verb is changing its tense.

a. The identities of the people were not revealed.

b. The glaciers in the north and the south pole are melting fast.

c. The atmosphere is geĴ ing polluted very fast.

d. The rare birds had leĞ their habitat before the team of experts could reach them.

e. I have broken my hand.

f. This building has stood the test of time.

g. We have been waiting for the bus since ę ve o’ clock.

The Finite and the Non-Finite Verb

One more distinction you should keep in mind is that between the ę nite and the non-ę nite

verb. The verb which carries the tense in a sentence is always the Finite verb and the others are

the non-ę nite verbs. Look at the following pairs of sentences—

a. the grass on the other side is always green.

b. the grass on the other side was always green.

c. the grass on the other side has been always green.

d. the grass on the other side had been always green until we crossed over and saw it for our-

selves.

We ę nd that in the ę rst pair, there is only one verb and naturally, it caries the tense. But in

the second pair, there is more than one verb, and when there is an auxiliary verb, it is the auxil-

iary that caries the tense. In a sentence, the verb which carries the tense is called the ę nite verb

and the others are called the non-ę nite verbs. If a sentence has only one verb, the main verb is

the ę nite verb. But if there is more than one verb, the verb carrying the tense is the ę nite and

the rest are non-ę nite verbs. It is necessary for you to be clear about these two types of verbs

to master the tenses that follow in the later sections.

The Forms of the Verb

Look at the following sentences:

a. We walk to the ground every morning.

b. The bus generally arrives on time.

c. The children played the whole day yesterday.

d. The executive members are planning for a meeting next month.

e. The students have seen the exhibition.

Communication Skills for Engineers

22

These ę ve sentences use the ę ve forms of the verbs that are used in diě erent ways to ex-

press the tenses. The ę ve forms are the following:

a. The base form: walk

b. The –es form (the third person singular): arrives

c. The past tense form: played

d. The be –ing form: planning

e. The have –en form: seen

These are the ę ve forms of the verb in English. It is important to note that these are the dif-

ferent grammatical forms of tenses. The tenses in English do not necessarily coordinate with

the times they express. Hence, it is important to see how these diě erent forms express the

diě erent time sequences. Given in the units that follow, are descriptions of the tense form and

the time sequences they express.

The verb “be” has ę ve forms—”is” “am” “are” “were” “was”. The ę rst three are

used for the present tense form and the last two for the past tense form.

The Simple Present Form

Look at the following sentences:

Rammohan drives the buses in this route.

Mahanadi Ě ows into the Bay of Bengal.

We experience the eě ects of ozone depletion every day.

He/she feels it is good in the long run.

They/we feel it is good in the long run.

The simple present tense, we have seen, uses two forms—the third person singular –es

form and the base form. We use it to indicate things that happen all the time and to show uni-

versal truths:

a. The earth goes around the sun.

b. The moon reĚ ects the rays of the sun.

c. The Ě ight takes oě at 5 pm.

d. Continuous working leaves one tired and exhausted.

Sometimes we also use the simple present to show how oĞ en we do things or how oĞ en

things happen.

a. Rohit sometimes plays cricket.

b. How oĞ en do you go to the dentist?

c. We usually take the road to the right of the park.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

23

We use do/does to express questions and negative sentences:

a. Do you believe in Darwin’s theory of evolution?

b. Rice doesn’t grow in cold countries.

c. We don’t oĞ en do things according to others wishes. Do we?

ACTIVITY

2. Fill in the blanks by using the right form of the verb given in brackets.

a. The shopping mall

(open) at 9am everyday.

b. We oĞ en

(see)

c. I have a jeep but I

(do) drive it oĞ en.

d. The river Amazon (Ě ow) into the Pacię c Ocean.

e. How oĞ en

(do) you write to your parents?

The Present Continuous Form

Look at the following sentences:

Don’t make so much noise. I am studying.

It is not possible to go out now. It is raining.

Have you heard the latest? Ram is ę nally writing the report.

Can you call the children inside? They are making a lot of noise.

The present continuous uses the “be (is, am, are)—ing” form of the verb. It is used to denote

action continuing the present at the moment of speaking.

a. Talk slowly. The patients are resting.

b. We have to go soon. Sheela is leaving.

c. Take an umbrella with you. It is raining.

d. Be careful. The vehicle is still moving.

It is also used to show action around the time of speaking.

a. You are working a lot today. Do you have a deadline to meet?

b. The population is rising very fast.

c. Your English is geĴ ing beĴ er. Keep trying.

ACTIVITY

3. Fill in the blanks, using either the simple present or the present continuous(be —ing

form of the verbs put in brackets. Indicate which of these situations are temporary and

which are permanent.

Communication Skills for Engineers

24

a. Arundhati is in India now. She (stay) at the Taj Banjara. She generally

(stay) there whenever she visits.

b. My parents

(live)in Delhi now. But we are from Bhubaneswar.

c. I

(teach) Physics. But this semester, I (teach) Mathemat-

ics too!

d. I generally

(drive) the bike. But because of a shoulder pain I

(drive) the car these days.

e. He never

(smoke) in public. Looks like something is diě erent today.

We ę nd in these sentences, that the combination of the simple present and present continuous

is also used to show the diě erence between the permanent and the temporary. There are some

verbs in English that can be used in the simple present form only, even when they denote the

present continuous action. For example, we can say

a. “I don’t understand you.” Not, “I am not understanding you.”

b. “I believe you.” Not, “I am believing you.”

The following are some of the verbs that cannot be used in the present continuous form.

want need like love belong see hear

realize mean forget remember prefer seem know

Simple Past

Look at the following sentences:

a. Look! it is raining again.

b. Yea. And it rained the whole of yesterday too!

c. I am hiring a taxi to go to work today. What about you?

d. I usually work from home on such days. Guess I’ll do the same.

The simple present generally uses the “–ed” to form the past tense. However, there are

many important verbs that are irregular.

a. leave—leĞ We leĞ for the party at 6 pm yesterday.

b. go—went I went to Chennai to see a friend of mine.

c. cost—cost This dress cost me a packet.

Questions and negatives in the simple present use did/ didn’t.

a. We walked home.

b. Did you walk home?

c. They didn’t walk home.

ACTIVITIES

4. A friend of yours has just come back from a holiday. You are asking her about it. Make

complete sentences, using the clues given.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

25

a. stay/cousin

b. what/place/see

c. meet/old friends

d. visit /library

5. Fill in the blanks, using past tense forms.

a. Rakesh

(not/bath) this morning before going to work. He simply

(not/have) time.

b. AĞ er the party, we (decide) not to eat anything because we

(be) not hungry.

c. She (be) not interested in the book because she

(not/understand) it.

Past Continuous

Look at the following sentences:

a. I saw Ramesh in the garden. He was reading a book.

b. We could not go out yesterday. It was raining all night.

c. Tom burnt his hand when he was cooking dinner

Like the present continuous, the past continuous too uses the “be—ing” form. But while

the former uses the “is”, “am”, “are” (the present tense forms) , the laĴ er uses “was” and

“were”(the past tense forms).

The past continuous is used to show action that continued for some time in the past. look

at the following sentences.

a. The child is tired. She was playing all day.

b. I have seen the plane. It was Ě ying very low in this area.

The past continuous is also used to show that some action was continuing when something

else happened and intervened.

a. I was working when the door bell rang.

b. We were walking when the car hit us from behind.

c. Mohan was cooking when I reached home.

ACTIVITIES

6. Make sentences using the words in brackets. Use them in the simple past or the past

continuous form.

a. (phone/ring/have/a shower)

My phone

.

Communication Skills for Engineers

26

b. (watch/a ę lm/television/news Ě ashed)

We were

.

c. (sleep/lightening/struck)

I was

.

d. (discuss/ the issue/ director/walk in)

We were .

7 Fill in the blanks using either the simple past or the past continuous.

a. Raghu

(fall) oě the ladder while he (paint) the

roof.

b. Smita

(take) a photograph when I (not/look).

c. I (break) a plate last night when I (wash).

d. Susan (wait) for me when I (arrive).

Present Perfect

Look at the following sentences:

a. Sita is looking for her keys. She cannot ę nd it.

b. She has lost the keys.

c. I have seen the ę lm. I am not really interested in seeing it again.

The present perfect tense uses the “have –en” form, or the past participle form with “have/

has”. It is used to show action that happened in the past but is connected with the present.

a. I have lost my papers. (I am still searching for them.)

b. Sonia has gone to Delhi. (She is still in Delhi.)

c. The team has arrived. (They are still here.)

Contrast this with the simple past tense.

a. I lost my papers. (But I managed the situation somehow)

b. Sonia went to Delhi. (She has come back last week)

c. The team arrived. (But they had to leave for security reasons)

We see in these sentences that both the present perfect and the simple past show past ac-

tion. But while present perfect suggests that the impact of the past action is still there in the

present, the simple past might simply focus on the fact that the action is over.

The simple present is oĞ en used with “just” to show that the action in question has

just been completed.

“Sheela has just completed the assignment.”

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

27

ACTIVITY

8. This exercise has situations. Read them and write a suitable sentence using the verb

given in brackets.

a. Rupa’s table was dirty. Now it is clean. (arrange)

She

.

b. Yesterday Sapan was playing cricket. But today his leg is in a cast. (break)

He .

c. The car has stopped. There is no petrol in it. (run out of)

The car has .

The present perfect is also used to show that you have not done something during a period

of time which continues up to the present.

a. I have never been to the 3D theatre.

b. I haven’t smoked for a year now.

c. I haven’t acted in a play since last September.

d. Suman hasn’t wriĴ en to me for a year now.

OĞ en, we use “for” and “since” with the present perfect tense.

“For” is used to show a period of time.

“Since” is used to show a point of time when the action began.

Present perfect is used with expressions like this morning/this evening/today/this week/

this term etc., especially when the period is not ę nished at the time of speaking.

a. I have wriĴ en ten pages since today morning.

b. We have seen ę ve accidents this week.

c. Sheela has taken twelve classes a week this term.

d. We have driven thirty kilometers this evening.

The present perfect is also called the tense of indeę nite time. It cannot be used with the

mention of specię c time. So when a specię c time has to be mentioned, we use the simple past

instead. Look at the following examples:

I ate out with my friends last week (not)

I have eaten out with my friends last week.

I saw the movie last week (not)

I have seen the movie last week.

I spoke to Meena on Wednesday (not)

I have spoken to Meena on Wednesday.

Communication Skills for Engineers

28

ACTIVITY

9. Answer the questions given, and ę ll in the blanks using the clues.

a. Have you seen the new canteen?

I

yet, but I’m .

b. Have you been to the new block of the department?

I

once, but I seen it for

now.

c. Have you bought your new car?

Oh yes! I have it with me since .

Present Perfect Continuous

Look at the following sentences:

a. i. Has the bus come?

ii. No, we all have been waiting.

b. i. The ground is wet. Did it rain?

ii. Yes, it has been raining since morning.

The present perfect continuous uses both the “have –en” and the “be—ing” form. It is gen-

erally used to show action that began and has continued for some time in the past. These are

actions that might have just got over or still continuing at the point of speaking. Look at some

more examples:

a. You are out of breath. Have you been running?

b. I have been talking to your teachers about your problem. They feel that………….

c. The roads are Ě ooded. It has been raining for four hours now.

d. I have been watching the TV since ę ve O’clock.

e. Aren’t you tired? You have been talking the whole evening.

Now, look at the following sentences:

a. Ranga’s clothes are soiled. He has been painting the ceiling.

b. The ceiling was white. Ranga has painted it.

In the ę rst sentence here, the emphasis is on the action itself. But the second emphasizes on

the completion of action.

a. There are dark circles around Rekha’s eyes. She has been working hard to complete the book.

b. Rekha has ę nished working on the book.

In the ę rst sentence here, the emphasis is on the act of Rekha’s working on the book. But in

the second, the emphasis is on the completion of the action.

The present perfect continuous, thus, is used when we want to stress on the act of doing

something. And only the present perfect is used when it is necessary to highlight the comple-

tion of the action.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

29

You can be a liĴ le ungrammatical if you come from the right part of the country.

—Robert Frost

ACTIVITIES

10. In the sentences given below, ę ll in the blanks by puĴ ing the verbs in the correct form

— present perfect or the present perfect continuous.

a. Look! Somebody

(spoil) the freshly painted wall.

b. I smell cooked food. Have you (cook).

c. Shekhar is an actor. He (appear) in several ę lms.

d. I (read) the book you gave me. But I (ę n-

ish) it yet.

e. I (loose) my key. Can you help me look for it?

11. Given below are some situations. Read them and make sentences using the words giv-

en. Use the have –en form for this.

a. Rupa is from Maharastra. Now she is traveling all over India to raise funds for char-

ity.

Rupa, from Maharastra, (traveling) all over India.

b. Jagan is a tennis champion. He began playing when he was 11. He is playing for

India still.

Jagan tennis since he was 11.

c. Jane and DiĴ y started making advertisements when they were in college. They are

still working together on several projects.

Jane and DiĴ y (work) together since their college days.

Past Perfect

Look at the following sentences:

a. When I arrived at the party, most of the guests had leĞ .

b. By the time we found the umbrella, the rain had stopped.

c. The car broke down yesterday. The brakes had failed earlier.

The past perfect tense uses the past form (had) of the “have—en” form to make sentences.

In the ę rst sentence here, we ę nd two time sequences. One is “arriving at the party”, and the

other is “leaving of the guests”. If “arriving at the party” is a past, the “leaving of the guests” hap-

pens before this past. The past of the past here uses the past perfect tense. Hence, it is the past

of the past. The same is found in the other two sentences too. In all these sentences, there are

two time sequences. One—the past, and the other—the past of the past. The past perfect is

used to show the past of the past.

Communication Skills for Engineers

30

Look at some more examples:

a. i. Was Sheela there when you reached the spot?

ii. No. she had already leĞ .

b. i. Could the police catch the thief yesterday?

ii. They tried their best but thief had leĞ much before they could arrive.

ACTIVITY

12. Fill in the blanks using the right form of the verbs given below.

a. Jim was not at home when I reached.

He

(already/leave)

b. The man was a complete stranger to me.

I (never/ see/before)

c. I was very tired when I reached home.

I

(play/tennis/wholemorning)

d. Mr Mathur no longer had his car.

He

(sell/last month)

d. I invited Margaret for dinner. But she could not come.

She

(promise/someone else)

The Future

In English, the future tense does not have a specię c form. It is generally expressed by using

a combination of various other tenses. Some of the ways of expressing the future time are as

follows:

By using the present continuous form with a future word.

a. I am going to meet the principal tomorrow.

b. The plane is leaving in an hour’s time.

c. We have to increase the speed. The shops are closing in an hour.

By using the modals to show possibility or probability in future.

a. It might rain in the evening.

b. The train should reach in two hours time.

c. I shall write the ę nal exams this year.

Both “will” and “is going to” express action one intends to do in future. But with a diě erence.

— will expresses impulsive decision, taken on the spot.

I will see to it that we don’t fail again.

— is going to expresses scheduled future action.

We are going to write to the Principal about this.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

31

ACTIVITIES

13. In these sentences you have to talk about your future plans. Use the right words to an-

swer these questions.

a. i. Which car are you going to buy?

ii. I am not sure. I

(Maruti Suzuki)

b. i. Is Raghu coming with us to the picnic tomorrow?

ii. He said he would try to. He

(even/bring/his sister) along

with him.

c. The computer is troubling me a lot. I

(take it/workshop.)

d. i. Where are you going to be transferred to?

ii. I

(have to/shiĞ /Bangalore).

14. Fill in the blanks in the following sentences.

a. I wanted to be the ę rst one to give the news. But I was too late. Someone

her. (already/tell).

b. I couldn’t open the door because someone

it. (lock)

c. Seema and Hari . I could hear them.(argue)

d. I about this for some time now. (know)

e. I signed the register and

to my room. (go)

f. I couldn’t take the bike because Ravi

it. (use)

g. When he warned them about the police, they the country.

(leave)

h. I think I

him somewhere before. (see)

i. when I reached her room, she the assignment. (do)

j. We for hours when I suddenly realized that something was wrong

with the engine. (drive)

THE PASSIVE

Look at the following sentences:

a. Rajiv has completed the experiment.

b. The experiment has been completed.

a. Many of the residents saw the Ě ying saucer.

b. The Ě ying saucer was seen by many.

In the passive form of the sentence, it is the object of the action that is highlighted rather

than the agent or instrument of action.

Communication Skills for Engineers

32

In the passive form, we use the correct form of the “be” verb (is/are/were/was) along with

the past participle form of the verb in the sentence. So we have forms like:

a. the work was done ...

b. the room was cleaned …

c. the house was built …

d. the inę ltrators were seen …

Apart from the “be” form, the passive also uses the “have / has been ………..” form. We

have forms like:

a. My bicycle must have been stolen.

b. All the trees in the area have been cut.

c. The monitor has been repaired.

d. The whole class has been punished.

Compare this to the active forms of the sentences:

a. The boys next door must have stolen my bicycle.

b. The illegal traders have cut all the trees in the area.

c. The new service engineer has repaired the monitor.

d. The Principal has punished the whole class.

As mentioned before, the active forms of the sentences focus on the agent of the action—

who has done the action is as important or sometimes more important than the action. In the

passive however, the action, not the doer, becomes important.

ACTIVITY

15. Fill in the blanks, using verbs of your choice in the appropriate passive form.

a. No decision on this maĴ er can

till next morning.

b. The book will have to

as soon as possible.

c. The injured man

to the hospital.

d. It is customary for the luggage to by the customs oĜ cials.

e. We all wanted to

before day break tomorrow.

The Passive is used when:

a. The doer of the action is not known.

b. The doer of the action is not important

c. The doer of the action prefers not to be known.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

33

Forms of the Passive

The following are some of the commonly used forms of the passive:

Simple present:

a. The rooms are cleaned everyday

b. People are injured in accidents everyday.

(Everyday, routine action.)

Simple past:

a. The documents were destroyed.

b. Patients were neglected.

(Action in the past.)

Present continuous:

a. Shops are being closed down everyday.

b. Problems in policy implementation are being discussed in detail.

(Action taking place at the time or around the time of speaking.)

Past continuous:

a. We suddenly realized that we were being followed.

b. Diě erent ways of lessening the border tension were being discussed when the war

broke out.

(Action that continued for some time in the past.)

Present perfect:

a. All of us have been invited to the party

b. Shyama has been elected president.

(Action was in the past time but it is still valid at the time of speaking.)

Past perfect:

a. The rooms looked much beĴ er. They had been cleaned.

b. We simply could not voice our protest. We had been asked to keep quiet.

(Action that took place before the past action mentioned in the sentences.)

ACTIVITY

16. Given below are some sentences. Read them and write down another sentence with the

same meaning. begin the sentence the way it has been suggested and note whether you

are using the active or the passive voice.

a. All the students should enter their suggestions in the register kept in the oĜ ce.

Suggestions

.

b. The Principal postponed the meeting due to his ill health.

The meeting .

Communication Skills for Engineers

34

c. Somebody might have issued the book if it was in the library.

The book .

d. A short circuit might have caused the breakdown.

The breakdown .

e. The architects are redoing the oĜ ce. It cannot be used right now.

The oĜ ce .

Grammar is a piano I play by ear. All I know about grammar is its power.

—J o a n D i d i o n

REPORTED SPEECH

Look at the following sentences:

a. i. “I am going home”, he says

ii. He says that he is going home

b. i. They said, “we are going on a picnic”

ii. They said that they were going on a picnic.

Direct speech is the actual speech of a speaker reported without any intervention. This is in-

dicated by puĴ ing the actual words within inverted commas, and separating it from the main

sentence with a comma. (see the sentences given above in the box). The reporting of this direct

speech to someone else needs a slight alteration of structure. This is called Reported speech.

Look at some more examples:

Charlie said, “I am thinking of going to Canada.”

Charlie said that he was thinking of going to Canada.

Raghu said, “I have been playing a lot of tennis.”

Raghu said that he has been playing a lot of tennis.

Sheela said, “I don’t know what Rajiv is doing.”

Sheela said that she did not know what Rajiv was doing.

Reported speech, we ę nd here, introduces a “that…“ form and changes the tense of the

reported clause. But this does not always happen. Diě erent tense forms make their reported

speeches diě erently. Remember that in a sentence where a speech is being quoted or reported,

there are two clauses with two ę nite verbs – one is the main verb that is linked with who did

the saying and the other talks of what was said. Given below are some verb forms and the

way they are transformed into the reported speech.

• When the main verb of the sentence is in the present, the present perfect or the future

tense, there is no change in the reported statement.

Tenses, the Active and the Passive Voice, and Reported Speech

35

“I haven’t done my homework,” she says.

She says that she hasn’t done her homework.

“The plane will land in ę Ğ een minutes,” the pilot has just announced.

The pilot has just announced that the plane will land in ę Ğ een minutes.

• When the main verb of the sentence is in the past tense, the verb of the reported speech

also is changed into the past. Look at the following sentences:

a. “The washing machine is broken,” he said

He said that the washing machine was broken.

b. “We have never been to Berlin,” they said.

They said that they had never been to Berlin.

c. “I am not feeling very well,” Shilpa said.

Shilpa said that she was not feeling very well.

d. “It was raining very heavily yesterday,” she said.

She said that it had rained very heavily that day before.

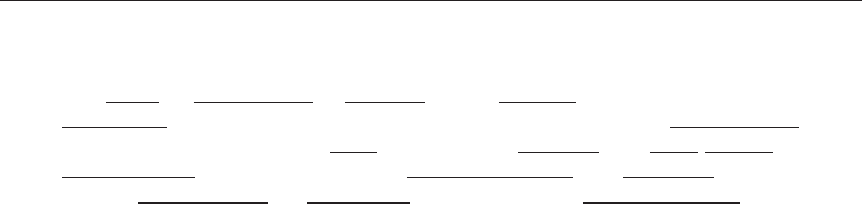

The following are the tense changes we ę nd when direct speech is converted to

reported speech:

simple present simple past

present continuous past continuous

past continuous past perfect continuous

present perfect past perfect

simple past past perfect

While changing the direct speech into the reported form the following changes too are

necessary.

shall should

will would

must had to

can could

tomorrow the next day

yesterday the day before

today that day

here there

this/that the

ACTIVITY

17. Change these sentences into reported speech, changing the words where necessary.

a. “I’m listening to the radio,” he said.

b. “I stayed awake the whole night aĞ er the party,” she said.